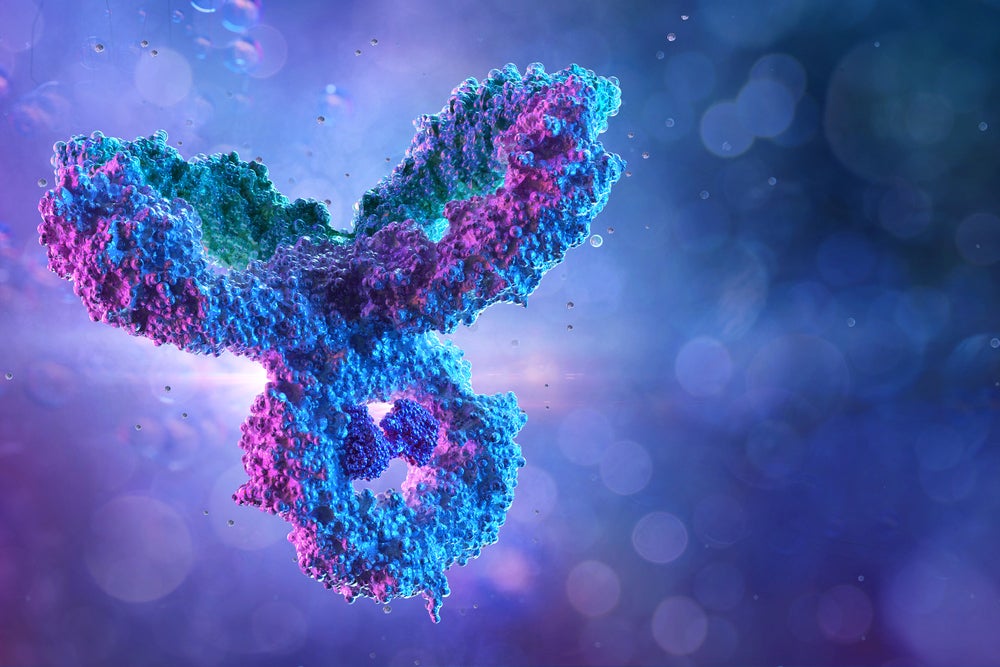

Antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) are a form of targeted immunotherapy. They are composed of three components: a monoclonal antibody (mAb) and a cytotoxic payload made from a chemotherapy agent, which are connected together using a chemical linker. The aim of ADCs is to deliver the cytotoxic agent selectively to tumour, therefore reducing extremely unpleasant off-target effects associated with traditional administration of chemotherapy.

Despite their vast potential to be ‘magic bullets’ in cancer, ADCs have presented a huge challenge to researchers particularly around getting the formula to balance the three-parts right. However, with ten ADCs now on the market, and all but one in the last 10 years and all but three since 2017, the promise of this modality is now bearing fruit.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Optimism about this therapeutic approach is clear given that despite the pandemic, 2020 saw multiple deals in the ADC space, which suggests there is significant investor and big pharma interest in this therapeutic approach. Examples include Merck’s $2.75bn acquisition of VelosBio and $1.6bn licensing deal with Seattle Genetics, and Gilead’s $21bn acquisition of Immunomedics.

To understand the renewed hype around ADCs, let’s look back at their history and consider what the future may hold for these targeted therapies.

1980s – 1990s: First successful attempts at ADCs

In the early 1900s, German scientist Paul Ehrlich theorized that a ‘magic bullet’ drug could be developed that selectively targeted a disease-causing organism with a toxin.

Around 80 years later in 1983, supported by successful development of mAbs in the 1970s and chemotherapy in the 1940s, researchers carried the first ADC human clinical trial using an anti-carcinoembryonic antigen antibody-vindesine conjugate in 1983. This ADC was deemed to be both safe and effective in the eight patients with various advanced metastatic carcinomas.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe 1990s then saw the emergence of the use of humanised mAbs in ADCs to further reduce the off-target effects. However, this early iteration of experimental ADCs were plagued with many issues associated with the three-component nature of these therapies. The issues ranged from unpleasant side effects to issues with the linker to challenges in delivering sufficient quantities of potent chemotherapy directly to the tumour site.

2000: First approved ADC, Pfizer’s Mylotarg

Despite these challenges, scientists and pharma companies continued to focus on developing ADCs throughout the 1990s. This led to Pfizer’s Mylotarg (gemtuzumab ozogamicin) being the first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Mylotarg was approved in 2000 for CD33-positive acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) patients aged over 60.

Mylotarg combined a humanised IgG5 mAb directed against CD33, a surface antigen on leukaemia cells, with a calicheamicin cytotoxin. In clinical trials, the ADC had been deemed safe and efficacious, however, post-approval studies and real-world experience actually suggested that it was in fact neither in some AML patients. This has been attributed to issues around the stability of its cleavable linker, which led to the premature release of the cytotoxic payload into the blood plasma, causing highly toxic effects.

This meant that within a year of approval, the FDA required Pfizer to place a black box warming to the drug’s packaging and in 2010 the FDA asked the company to remove the drug from the market. After lowering the dose and adjusting the dosing regime, Mylotarg was re-approved by the FDA in 2017 to help resolve the remaining unmet needs in AML.

2010s: More approvals, but setbacks remain

One year after Myoltarg was removed from the market in 2010, a second ADC was approved by the FDA. Seattle Genetics’ Adcetris (brentuximab vedotin) includes an anti-CD30 mAb connected to a highly tubulin inhibitor monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE). Adcetris is indicated for patients with relapsed or refractory CD30+ Hodgkin lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

The ADC relies upon a special, second-generation cleavable linker designed to remain stable in the blood stream and encourage an effective bystander effect that means the drug can kill both CD30 positive and CD30 negative tumours. Unfortunately, Adcetris carries a blackbox warning for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and causes unpleasant haematological side effects, including neutropenia.

Adcetris was followed in 2013 by the approval of Roche/Genentech’s Kadcyla (trastuzumab emtansine) for patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. This approval brought the first ADC to the solid tumour space. Kadcyla combines mAB trastuzumab and chemotherapy emtansine. It relies on an optimised non-cleavable linker, which means that it has a lower toxicity profile, but no bystander effect. Despite this tolerable safety profile, Kadcyla carries a blackbox warning for hepatotoxicity, embryo-foetal and cardiac toxicity.

These blackbox warnings make it clear that although the benefits of ADCs are deemed to outweigh the risks, there remained some major issues with these products, particularly linked to the linker’s stability and carrying sufficient quantities of the cytotoxic payload to the target. This also helps to explain why in the 2010s numerous ADC development programmes had to be abandoned.

2017-20: Enter third-generation ADCs

Over the next decade, companies and researchers focused on finding ways to further improve the linkers and payload challenges. After learning that second-generation ADCs were not well configured during the manufacturing progress, researchers began to focus on better bioconjugation of the ADC components, particularly the linker.

After two new approvals in 2017 and 2018, there was a flurry of approvals in 2019 with three new ADCs entering the market: Roche’s Polivy (polatuzumab vedotin-piiq), Seattle Genetics and Astellas’ Padcev (enfortumab vedotin) and AstraZeneca and Daiichi Sankyo Enhertu (trastuzumab deruxtecan). Many believed these five approvals in two years suggest a comeback for ADCs as lessons had been learnt from previous setbacks to optimise these products.

Both Roche’s Policy and Astellas/Seattle Genetics’ Padcev rely on the optimised cleavable linker developed for Seattle Genetics’ Adcentris. While AstraZeneca/Daiichi Sankyo’s Enhertu rely on tetrapeptide-based linker, which aims to break down enzymes present in tumour cells. Enhertu was also optimised to allow it to carry large amounts of cytotoxic payload while remaining tolerable to patients.

In April 2020, Immunomedics’s ADC for triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) Trodelvy (sacituzumab govitecan) was approved by the FDA. Trodelvy targets Trop-2, which is over-expressed on TNBC, using a mAb to deliver the cytotoxic payload SN-38 to tumours. Immunomedics has spent decades refining its ADC platform and has developed a differentiated hydrolysable linker that means Trodelvy does not have to compromise on safety and efficacy. This linker also, importantly, creates an effective bystander effect in the tumour micro-environment and can deliver large quantities of SN-38 directly to tumours.

2020s: A bright future for ADCs

Industry interest in ADCs as a therapeutic modality has been encouraged by the success of these third-generation products. Despite the disruption of the pandemic, 2020 saw multiple large ADC-related deals. The most notable is Immunomedics’ being acquired by Gilead for $21bn just six months after the approval of its first drug, Trodelvy. Gilead’s release notes that Trodelvy will be a cornerstone product in Gilead’s oncology pipeline, alongside other innovative products such as cancer CAR-T therapy Yescarta. Immunomedics is also studying Trodelvy in other types of breast cancer and urothelial bladder cancer.

In addition, following Enhertu’s success – the drug was recently approved for a second oncology indication – AstraZeneca decided to expand its collaboration with Daiichi Sankyo for other ADCs based on the same technology; this deal involves up to $6bn in staged and milestone payments for Daiichi Sankyo.

Another reason for optimism about the future of ADCs is this therapeutic approach has a healthy landscape of innovative small biotechs. Most of these are focused on expanding ADC’s therapeutic potential by further optimising the synergy between the three components. Notable examples include UK-based ADC Bio, which entered into a strategic partnership with Sterling Pharma Solutions in December to encourage innovation in the ADC space, and California-based VelosBio with a ROR1-focused portfolio across various tumour types.

Recently, there have also been moves to investigate the promise of this therapeutic approach outside of oncology. Although internally focused only on cancer, Swiss biotech Araris, which recently raised $16.6m in a seed round, believes its optimised ADC linker technology could be applied outside of oncology as anti-inflammatory agents in autoimmune conditions. Araris is looking for partners to study its ADC technology in these non-oncology indications.

Another example is Allergan which is working on an anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) ADC for adults with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis; the product is called ABBV-3373 and was originally developed by AbbVie.

AbbVie president and vice-chairman Michael Severino noted: “This proof of concept study demonstrates clinical activity of the TNF-ADC platform and its potential to advance the standard of care for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Based on these results we will advance the development of the TNF-ADC platform in rheumatoid arthritis and begin clinical studies in other immune-mediated diseases.”