Decentralization is one arrow in the quiver to modernize clinical trials.[1] Yet, owing to the varied approaches and possible components that can be brought to bear under the rubric of decentralization, a singular and unifying definition is elusive. Even the name ascribed to the movement has been in flux: mobile, virtual, digital, site-less, and remote, just to name a few. Perhaps this struggle to characterize the vision has abetted slow implementation, despite the FDA’s stated interest in incorporating and expanding such methods into protocol design.

Decentralized clinical trials (DCT) are defined as studies “executed through telemedicine and mobile/local healthcare providers, using processes and technologies differing from the traditional clinical trial model.”[2]

Remote decentralized clinical trials (RDCT) are defined as “an operational strategy for technology-enhanced clinical trials that are more accessible to [participants] by moving clinical trial activities to more local settings.”[3]

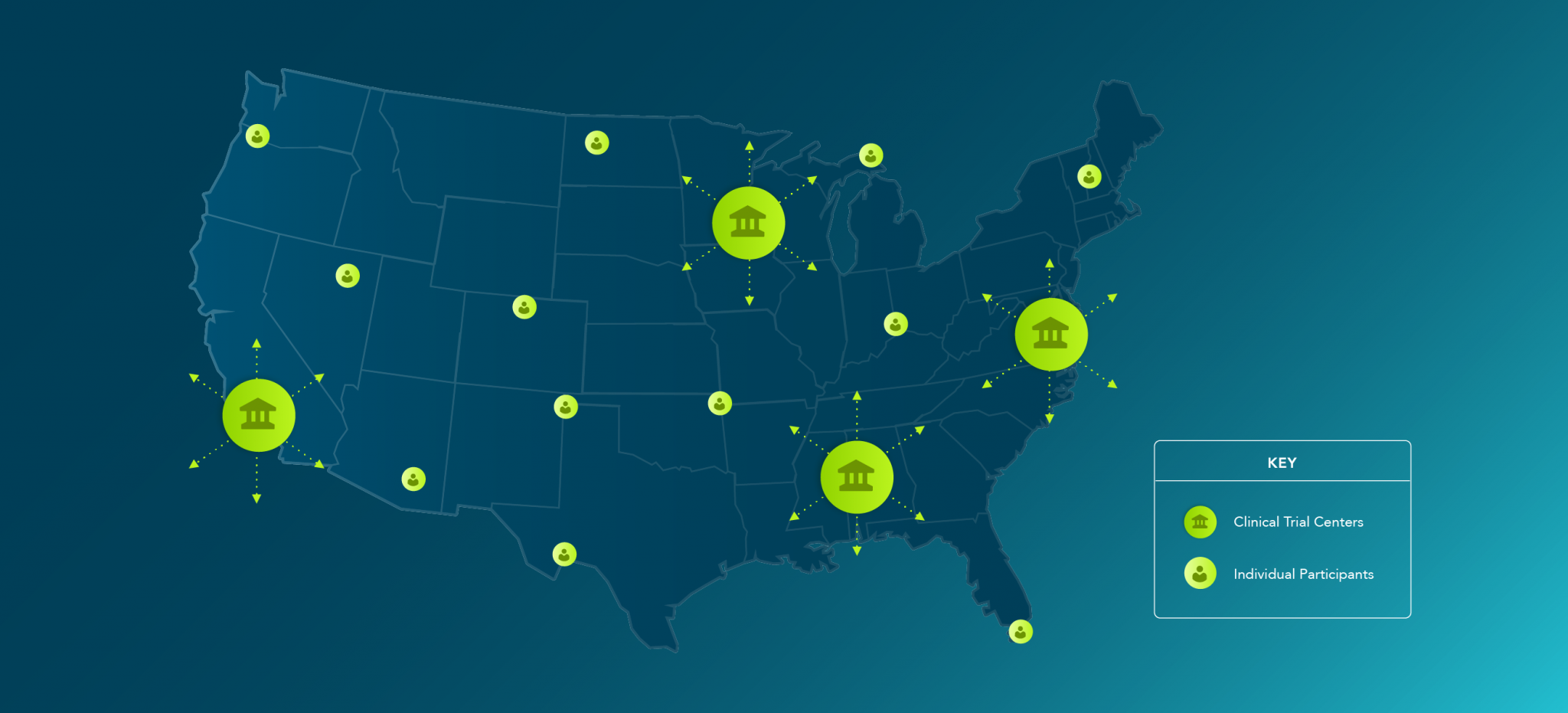

Technology is the linchpin. Decentralization, of course, is a matter of perspective. Certainly, participant-centricity should be at the forefront of our minds in defining and shaping the relative impact of a clinical trial. On the one hand, participation is diffused outside the trial site as participants avoid the inconvenience of traveling to traditional sites with the same frequency. Where the site used to be a proxy for the participant, as the means through which the participant engaged the clinical trial, participants can now engage from their home or preferred location. If this is an abstruse centralization from the vantage of each individual participant — into their home — there are components of decentralization benefitting from more obvious centralization, including clinical trial oversight, whether through remote monitoring, fewer clinical investigators, or independent ethics review.

Nevertheless, the life sciences industry is making strides. Headlines are replete with the adage attributed to Plato, necessity is the mother of invention.[4] More than the creative flash is needed though. Where many were reluctant in the face of perceived regulatory uncertainty in the past, the public health emergency has also afforded the FDA with the opportunity to meet the challenge and provide guidance to balance the field, rather than looking solely to industry leaders to forge ahead on an ad hoc basis.

To touch on a few examples, the FDA clarifies the extent to which involved local healthcare providers (HCPs) might not be considered sub-investigators and need not be listed on the FDA Form 1572. The general standard of “direct and significant contribution to the data” remains, but procedures that do not differ from routine clinical practice do not qualify (as opposed to drug response assessments or procedures performed unique to the protocol and distinct from routine medical care).[5] Instead, these HCPs should be documented in site records, such as the delegation log.[6] Of course, the IRB-approved protocol should describe the particulars surrounding administration of the investigational drug.[7]

Related, the FDA emphasizes that investigators must ensure access to necessary documentation contained in the participant’s medical record, especially if the HCP administering the investigational product (IP) is not considered a sub-investigator. Consequently, the investigator must obtain consent from the participant to access trial-related data in the medical record (e.g., vitals and routine symptom evaluation associated with administering IP).[8] The FDA also recommends the investigator communicate the intent to request these records from the HCP as soon as possible.[9]

The FDA confirms that IP may be shipped from a central distribution site directly to an HCP or — risk profile permitting — to a participant, provided such shipping occurs under investigator supervision using procedures to assure accountability and product quality (i.e., that IP storage conditions, as defined in the protocol, were maintained during shipping and that the IP packaging was intact upon receipt).[10] The FDA also provides recommendations for disposing unused IP in the absence of direct site involvement.[11]

The FDA, going further, has sought to directly facilitate remote administration of clinical trials with access to the MyStudies application for electronic consent.[12] Also, illustratively, the FDA has doubled down on making accessible, low risk digital health devices, specifically in the context of mental health.[13]

However, as with those promulgated by many government offices,[14] these guidances, typically by their own limitation, are tethered to the duration of the pandemic. It is important to maintain the momentum, leveraging innovation and experience, to sustain adoption. As similarly integral to intellectual property rights, consistency in interpretation and application of standards provides entrepreneurs with a level of comfort in business planning. The same holds true in planning for clinical trials. Clarity – through consistency – in the regulatory landscape post-COVID-19 will go a long way in meeting industry expectation and solidifying gains. Whereas, a significant rollback could jeopardize the level of comfort with decentralized methodologies and best practices beginning to emerge—not to mention what, if any, significant and lingering impact the pandemic will have on participants’ general attitudes toward wider socialization and exposure, where convenient and safer alternatives have been introduced.

Watch the free virtual symposium, Adapt & Succeed in a Decentralized Landscape, here.

Decentralization, by no means the panacea, will not cure all that ails clinical trials. Yes, these methodologies can create efficiencies and lower the bar to participation in the long run and have the promise to reduce ethnic and other disparities in clinical trial participation. Still, as healthcare in parallel becomes more decentralized, many of the same barriers to clinical trial participation will exist and new challenges arise — whether they persist remains to be seen. Clinical trial awareness, among providers and patients alike, remains a barrier. New challenges posed include simple verification of a participant’s identity and whoever else may be present during a telemedicine visit.[15] Telemedicine laws and payer coverage determinations are increasingly accommodating of telehealth, moving toward service and payment parity.[16] This push will potentially enable more providers to participate in clinical research.[17] Increased diversity among investigators and study staff could, in turn, lead to similar gains in participant populations. Will service and payment parity result in health parity and equal access to clinical trials? Or, could we create a winnowing of available investigators and participants due to limited technical capacity, further exacerbating justice and equity concerns in research?

There is more consensus and optimism surrounding clinical trials, for sure—particularly now. DCTs should have their most profound impact on participant retention, engagement, and satisfaction. To truly realize the inclusivity potential of DCTs, stakeholders should be prepared to continue to support infrastructure and provide technology to prospective participants—at least for the foreseeable future—as necessary to level the field.

It is important to keep in mind that DCTs are not one-size-fits-all and that, often, a hybrid approach will be necessary, particularly when rolled out across multiple jurisdictions where laws, technological uptake, and populations will vary. Importantly, where hybrid models are implemented, sponsors should balance differences in the conduct of a clinical trial against unnecessary or even confounding variability in the data generated. Additionally, investigators should inform participants about the relative differences where the decentralized components are optional (e.g., are there unique confidentiality risks associated with a digital health device or home health service?). Needless to say, this complicates planning until foundational procedures (e.g., plans for risk assessment, monitoring, IP accountability, training, privacy and security, etc.) are developed and vetted through transformative experience. As ever, involving all stakeholders (e.g., participants, investigators, regulators, etc.) early in the planning process is the best way to mitigate the complexity and ensure successful implementation of DCTs.

Advarra Consulting provides leading-edge research and development strategy and technical advisory services to stakeholders across the clinical research ecosystem, including sponsors, CROs, government entities, and the research site community. Our expert consultants are experienced industry practitioners—alumni from some of the most respected companies in the world—offering their extensive hands-on experience to provide outcome-oriented solutions across the product development lifecycle, with centers of excellence specializing in Quality, Regulatory, Clinical, and Research Administration and Human Research Protection Program (HRPP). Contact us to learn more.