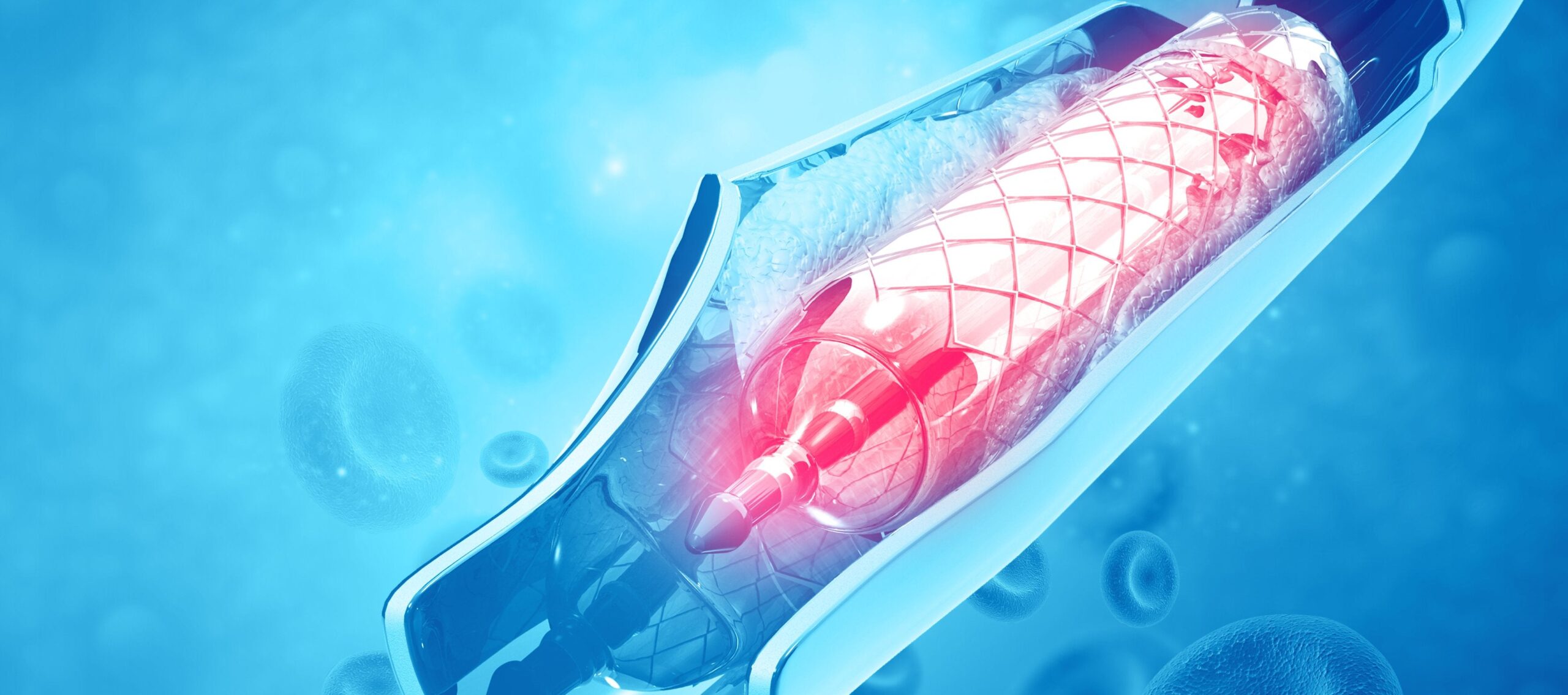

Thrombectomy is, by many accounts, a game-changing procedure in the treatment of strokes. It involves using a specially designed clot removal device or stent, manipulated through a fine catheter in an artery in the groin, to pull or suck out a clot lodged in an artery in the brain to restore blood flow.

If delivered quickly, research has found that a thrombectomy can significantly reduce the risk of death or disability from a stroke. Despite this, the procedure’s roll-out across the UK has been much slower than elsewhere in Europe and the US.

Here, Martin James, consultant stroke physician at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, and honorary clinical professor at the University of Exeter Medical School, gives his thoughts on how to overcome some of the challenges behind this slow uptake.

What makes thrombectomy such an exciting procedure?

Thrombectomy represents an extraordinary leap forward in the treatment of the most disabling and most expensive form of stroke – not just in human terms but in terms of costs to the NHS and society. I suppose in medicine we have grown used to incremental progress. We make tiny, little steps over longer periods of time. Each drug is just that little bit better than the last, and we have become accustomed to that slow rate of progress.

Thrombectomy is different: it’s a giant leap forward. Take a condition like a proximal middle cerebral artery stroke, which has got a terrible prognosis, one far worse than most other conditions in acute medicine. Thrombectomy effectively transforms the prognosis from terrible to the prospect of a cure, and that’s a once-in-a-generation sort of medical advance. The idea that someone can have a major stroke but recover to continue to lead an active and independent life afterwards is made into a reality with this procedure.

What are the main reasons for the roll-out of thrombectomy being so slow across the UK?

There are many challenges around the widespread implementation of thrombectomy, including those relating to geography, organisation and NHS funding. In terms of staffing, providing a round-the-clock, 24/7 service requires a reliable and responsive rota. There is generally a lack of trained neurointerventionists capable of performing the procedure in the UK.

Then, of course, the UK has a proud heritage of evidence-based medical practice. And that’s one way that we control the costs involved in providing the widest possible healthcare to the population. NICE [the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence] decides what constitutes an intervention that can or should be provided on the NHS, and what doesn’t. That’s only fair, but it does mean that when there’s a radical change in the management of a condition like stroke we, as a nation, are less well prepared than others. Thrombectomy is still a young procedure and so when NICE approved the procedure in the NHS in 2016 the numbers were very small, and limited to just a few specialist centres.

What is, in your view, the best way of ensuring thrombectomy services are available to the maximum number of people nationwide?

Having the right infrastructure and the right staff are vital to the roll-out of thrombectomy. It’s a mix of things, really. You’ve got to be strategic with where you develop specialist comprehensive stroke centres, so that they will reach the maximum catchment population quickly. You’ve got to modernise hospitals, particularly interventional labs. You’ve got to invest in the research and training required to hone the thrombectomy procedure and create a pipeline of people equipped to perform it.

When we talk about infrastructure, as well, we don’t just mean in terms of physical centres. We mean in terms of the support staff and organisation required to help the neurointerventionists perform their job. People such as neuroanaesthetists, radiographers and lab nurses are just as important in making a thrombectomy service happen. This means investing in the requisite numbers of radiologists who can carry out scans to identify patients suitable for the procedure, too, and there’s a severe national shortage of radiologists.

What are the key staffing and training challenges for thrombectomy roll-out?

The long and short of it is that in the UK we have fewer than a hundred operators who can actually perform the procedure. While there are now several 24/7 thrombectomy services, the majority are not. Some are limited to office hours, for staffing reasons, and, of course, you can’t guarantee that someone is going to have a stroke during a certain time frame or indeed necessarily near to a specialist stroke centre.

We do need to look into encouraging thrombectomy as a specialism earlier in the pipeline, at the medical school and trainee level. But the issue with this is that it takes a long time to wait until these trainees are fully trained and ready to carry out the procedure. It could be up to ten years until they actually independently treat a real-life patient.

So we have to look at more immediate, rapid staffing solutions. That might involve recruiting from abroad. There needs to be a conversation around retraining people with other, comparable, specialisms so that their skills might be transferred and applied to thrombectomy. This is, naturally, not an overnight process, and would take time, but it would take less time than waiting for trainees to graduate. If we can promote an additional, mid-career qualification or credential in interventional neuroradiology that might enable other specialists to make the move.

There are some radiologists or cardiologists who, in my view, already have the necessary catheter skills, who are treating other conditions. There may be scope for them to retrain and upskill to treat the cerebral circulation. They’ve got the essential, basic skills, and with the right, additional training in interventional neuroradiology could provide another talent pool from which to recruit.