Internet of things (IoT) technology has boomed over the past decade, particularly so in the medical industry over the past three years.

The Covid-19 pandemic led to an expansion of telehealth products, and the rapid dissemination of wearable technology means that continuous health data is more available than ever before.

British-headquartered healthcare and health insurance provider Bupa has invested heavily in IoT and artificial intelligence (AI) infrastructure, focusing on a vertical integration made possible by its unique position as payor and payee.

Speaking to Pharmaceutical Technology, Global Healthcare Transformation Director Dr Arun Thiyagarajan explains: “One of our key differentiators is that we have a vertically integrated model in which we pay and also provide care for our customers. So, it really is in our interest to prevent illness […] that gives us the unique permission to delve into these types of areas to see how we can provide value to them because providing value to them is providing value to us.”

Apps, AI and IoT

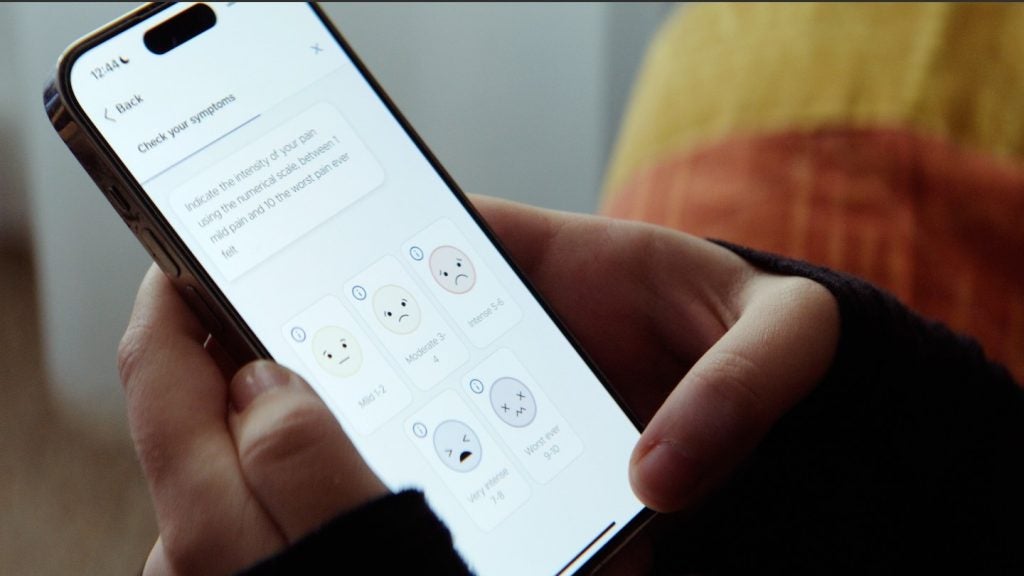

The company is making good use of this permission, having expanded its offering with app-based mental health support, AI-assisted melanoma tests and heart check-ups informed by retinal scans. The first two of these solutions are available at home, utilising internet-connected devices such as smartphones and wearables.

The melanoma test involves sending a kit including a smartphone and a dermatoscopic lens to the patient’s house. They are then entrusted with taking photos of their own moles or lesions and uploading them to a secure app stored on the phone. This enables the company to triage without needing to use doctors’ valuable time.

Although Thiyagarajan makes clear that in the case of melanoma any risk rated as “average or above” would go to a professional, the initial check is done by an AI co-created by Skin Analytics. The AI-focused biotech is also partnered with the UK’s public health service, the NHS. The software checks the images uploaded against a database of thousands of photos to determine the likelihood of cancer, with a 96% accuracy rate according to the company’s website.

Bupa is also making use of wearable technology to expand monitoring possibilities for patients. In Spain, another one of the company’s key markets, it is using wearables in combination with AI to track joint movements in post-operative patients, enabling automated systems to determine their quality of recovery.

This system, Thiyagarajan says, helps patients “live their lives to the fullest.” It also comes with the benefit that Bupa’s doctors can see more customers in less time.

Its AI-powered mental health care offers a similar value proposition. Rather than aiming to treat longer-term depression, this service is aimed at prevention, a key factor in stemming the tide of mental illness. Accessible through the Bupa mobile app, the tool combines standard mental wellbeing questionnaires asking about mood and thought patterns with wearable data that tracks exercise and sleep patterns.

By studying these two factors in tandem, the app is apparently able to learn and detect patterns that form between the two, noting for instance the impact that a reduction in regular sleep may have on an individual’s mood. This then guides the user toward “modular material that is specific for the prediction and bespoke to that individual.”

Digitisation in the health market

Bupa is by no means the first to offer mental health support via an app-based service, nor even the first major health company to put serious money into the concept. However, the power of vertical integration may help it succeed where others have failed.

Path Therapeutics, once the poster child for the expanding telehealth market, went bankrupt in April of 2023, citing issues convincing payors to fund its service. Whilst there may have been other factors at play in that case, it is true that convincing insurers to expand treatment coverage, particularly for preventative healthcare, is difficult.

Bupa on the other hand has a guaranteed payor in itself, meaning that it knows there will be a market for its product. Thiyagarajan notes that the costs of digitisation “will be incurred anyway, it just depends on where we would choose to invest it.” By largely targeting innovations outside the hospital, Bupa hopes to get ahead of the curve in what it clearly sees as an emerging market.

There is one other group to consider in this brave new world: the patients. When asked about potential patient concerns over having triage initially performed by an AI, Thiyagarajan responds that “customers are probably more likely to be anxious about diagnosis by artificial intelligence if they think that that's the only thing that's looking after them,” but “having said that, if you put both in the journey at the right points, I think, our general experience is that […] satisfaction levels increase.”

The combination of IoT technology and AI is still in its infancy and its long-term efficacy still remains to be proven, but if Bupa gets its way it will remain at the forefront of an exciting – and potentially lucrative – field.