After the turbulent reaction to Lykos Therapeutics’ failure to get its MDMA formulation approved, clinicians and industry leaders working with psychedelics are now mapping the path ahead for regulatory success. At the forefront of these efforts is the need to avoid the pitfalls in Lykos’s journey.

On 9 August, Lykos Therapeutics, the front-runner in MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) therapies, announced that its debut candidate’s NDA was rejected by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Although the momentum for MDMA therapies hit resistance, experts maintain not all is lost, and there still could be a path for MDMA and psychedelics to get to patients.

Lykos's failed NDA

On 4 June, a Psychopharmacologic Drug Advisory Committee of the FDA met to discuss Lykos Therapeutics’ new drug application (NDA) for MDMA capsules to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In a vote of nine to two, the committee decided that the available data, largely from the MAPP1 (NCT03537014) and MAPP2 (NCT04077437) trials, did not show adequate efficacy for treating PTSD. They also voted 10 to one that the therapy’s benefits did not outweigh its risks.

The Phase III MAPP trials, which drove the NDA, enrolled 221 PTSD patients. Patients participated in three eight-hour therapy sessions over 12 weeks and were randomised to receive either the company’s proprietary formulation of MDMA or a placebo during sessions. The trials met their primary endpoint—a change in symptom severity from baseline according to the CAPS-5 or clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-V scale. But the committee raised several issues with the data package.

Firstly, members felt the risk of using an MDMA formulation as a therapeutic was not fully characterised. Rectifying measures were suggested by the committee; for example, increasing the supportive trial staff, gathering more comprehensive data, and instituting an updated risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS).

Additionally, the committee noted problems with the study blinding. They worried patients would likely know which formulation they had received, given how apparent the effects of psychedelics are to those under their influence. Potential expectations of benefit among these patients led regulators to question the benefits of MDMA supposedly demonstrated.

The committee meeting was followed by an official rejection of the drug’s approval, wherein the FDA asked the company to conduct an additional Phase III trial. Less than two months later, the company announced 75% of their staff would lose their jobs, and subsequently several senior executives, including CEO Amy Emerson would step down.

Although Lykos declined an interview, a company representative told Pharmaceutical Technology, “The reorganisation was done to best support the company as it works to address the resubmission of our NDA”, which the company maintains is still its focus.

Independent perspectives

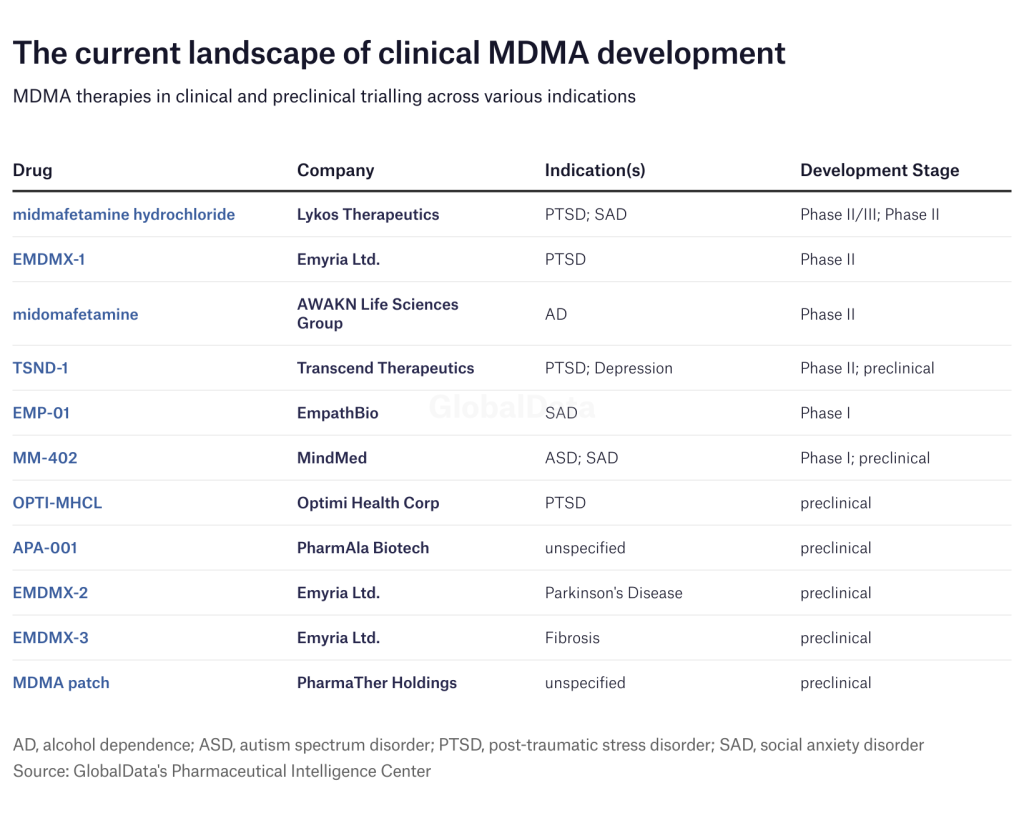

Lykos’s MDMA candidate was the closest to FDA approval, but by no means was it the only one. Companies like Emyria, AWAKN, and Transcend also have candidates in Phase II trials.

Dr. Ryan Henner, psychiatrist at Harvard Medical School, said the issues faced by Lykos may not be unique to the company because “people who are involved in this space are passionate about trying to bring these therapies to market.” He cited issues with Lykos’s trial approach, including “implicit, and perhaps explicit, discouragement of reporting side effects from the participants, a sense of advocacy for the treatment on the part of the company”.

According to Henner, much of psychedelic medicines’ success lies in culture; “If we end up in a cultural-political climate that highly values dogma and control, psychedelic treatment will not be allowed to exist broadly. It just changes people's minds too much. You can't control it. If we remain in a relatively free society, I think that we're more likely to see that sort of treatment.”

In such a backdrop, the FDA rejection may not have been fully unexpected, since some challenges, like with data blinding, are well understood in the field.

“There are other places in medicine where blinding is not possible,” says Brian Pilecki, PhD, a psychiatrist with the Portland Psychotherapy Clinic, Portland, Oregon. But this may not be a critical factor blocking the approval of psychedelics, since creative approaches like replacing inert placebos with amphetamines to elicit similar experiential changes to MDMA can be employed, according to Pilecki.

An important difference between MDMA and other psychedelics is that the former is administered within a broader course of psychiatric therapy, says Dr. Eric Vermetten, clinical psychiatrist at Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands. According to him, MDMA acts as a catalyst, inducing a mental state more receptive to traditional therapy. This was the role the drug served in the Lykos trials, which incorporated MDMA into a recognisable, therapist-led course.

However, this was a key issue raised by the FDA committee. The involvement of therapists throughout treatment in conjunction with MDMA dosing left concerns that functional unblinding of patients might also affect therapists who knew which of their patients received treatment. Any differences in the way therapists might have treated patients in either study arm would cast further uncertainty on the trial’s results.

Despite these challenges, there is stout confidence in psychedelics among researchers. When asked about the prospects of these drugs, given the news from Lykos, Vermetten was resolutely optimistic. “I think the transformative capacity that psychedelics have for viewing yourself and how you relate to the world is incomparable with other medicines.”

Market opinion

Lykos is not alone in MDMA research, as several other companies continue to push their candidates towards approval. New York-based MindMed is developing its MDMA therapy MM-402 for treating autism spectrum disorder.

Dr. Dan Karlin, CMO at MindMed, views concerns raised by the FDA committee as “Lykos-specific issues, study conduct-specific issues.” He believes MindMed’s methodology will side-step the patient and rater-blinding problems central to Lykos’ NDA rejection. Though Lykos had to demonstrate a drug effect while part of a multi part treatment, others may not use the same approach. “Rather than doing psychedelic-assisted therapy, this [MM-402] is drug treatment only,” says Karlin.

Additionally, incorporating dose response analysis, expectancy assessment, blinded central raters, and excluding participants with prior psychedelic use are among measures that can shield MindMed from the failings of Lykos, says Karlin. “It will be important, whether it's Lykos or some other company, and whether it's MDMA or some other substance, for some other psychiatric indication, to really maintain a strong, explicit neutrality in regards to the potential for the treatment to work,” says Henner.

Nonetheless, Karlin remains confident in getting psychedelics approved and, cited growing interest in psychedelics among groups supporting veterans with PTSD as a route to bipartisan political acceptance of these therapies.

It is not just pharmaceutical companies looking closely at this space. Dr. Aron Tendler is the CMO of GrayMatters Health, a company that employs EEG (electroencephalogram) signals to help PTSD sufferers manage their symptoms. He does not view psychedelic therapies as competitors, but as potential collaborators. He posits that psychedelics could restore motivation in PTSD patients, a known challenge, that could aid the use of the company’s Prism technology.

The need for new treatments is another critical factor. Pilecki says, “We're in a mental health crisis in the US and other Western countries. This is an alternative; this could really help alleviate a lot of suffering that's out there in the world.”