Researchers have found a way to test cancer drugs on patient-specific ‘mini tumours’ grown in the lab to help doctors tell in advance what drugs will work.

Published in Science and conducted by researchers from the Royal Marsden and the Institute of Cancer Research, the study looked at whether mini-tumours could be used to predict how patients would respond to treatment.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

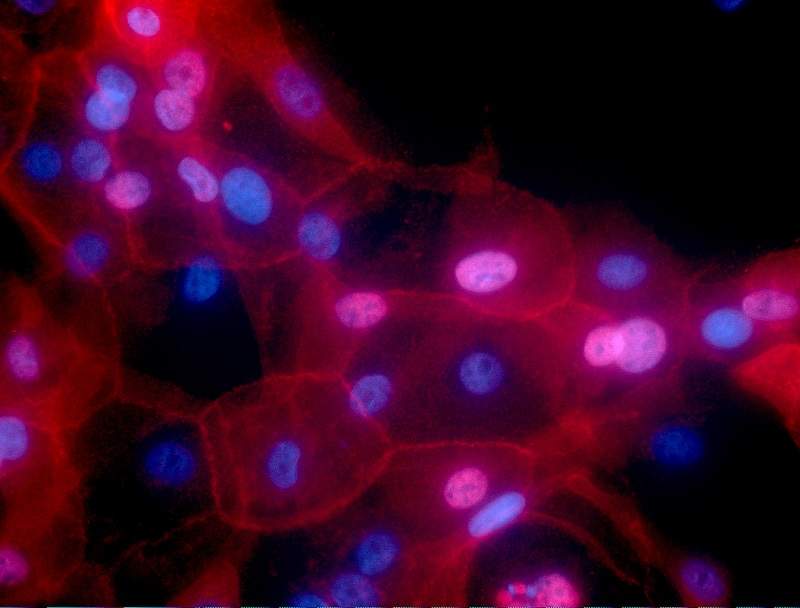

The mini tumours were grown from tissue samples from 71 patients with advanced bowel, stomach or bile duct cancer whose tumours had spread round the body. The tissue samples were then grown inside a gel to create miniature ‘organoids’ with a 96% similarity to the original tumours. Researchers then tested 55 cancer drugs on cells from the samples.

Researchers treated each mini tumour with the same drug previously given to the patient in order to test whether they responded in a similar way. By observing how the organoids reacted to different drugs, researchers were able to predict with 88% accuracy which drugs would be effective in producing a response in patients. Researchers also found that if the drug failed in the organoids, it failed 100% of the time in the patient.

Mini tumours could be used to test cancer drugs without exposing patients to unpleasant side-effects for drugs that are not guaranteed to effectively treat their cancer. The technology also has the potential to reduce the use of animal testing and lower the amount spent on ineffective treatment.

Mini tumours were also more effective at predicting drug response than analysing the DNA code of the patient’s tumour alone.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThis method cannot be used to test treatments that work by targeting the environment around the tumour.

Study leader and team leader in gastrointestinal cancer biology and genomics at the Institute of Cancer Research Dr Nicola Valeri said: “We were able to look in incredible detail at how tumours responded to drugs–including patterns of gene activity and mutation, and even how the cancer would evolve in response to treatment. We looked at tumours from patients with cancers of the digestive system, but the technique could be applied to a wide variety of cancer types.

“We need to further evaluate its potential in larger clinical studies, but it has the potential to help deliver truly personalised treatment–and avoid the reliance on trial and error for many patients when clinicians give them a new cancer drug.”