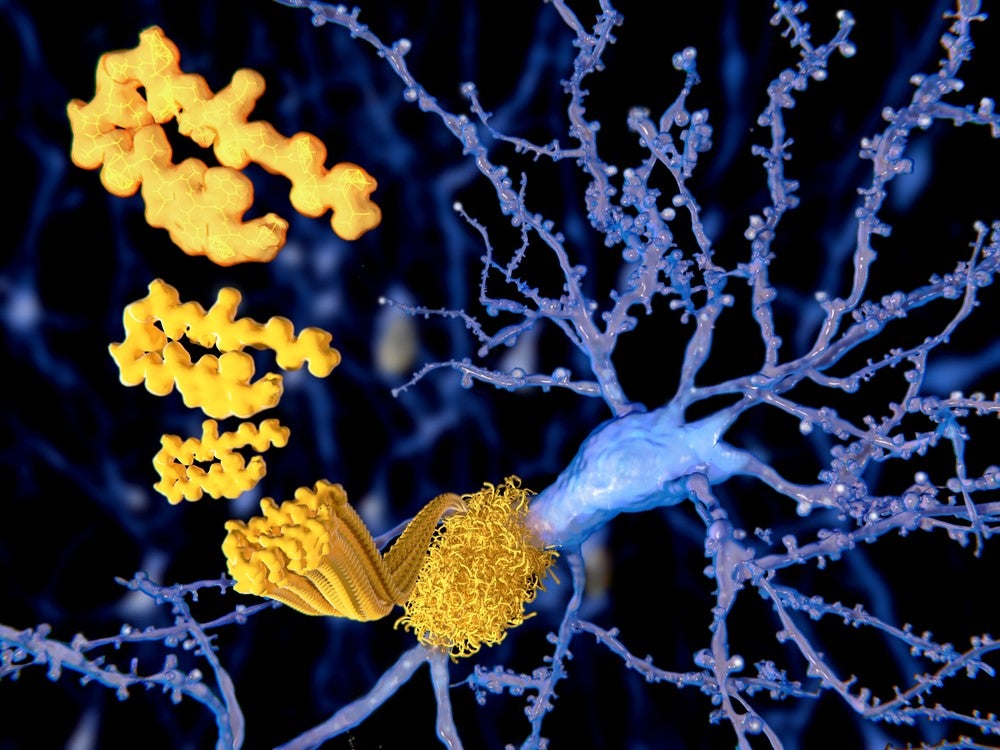

Believed to be caused by the build-up of plaques in the brain consisting of fibrillary amyloid beta (ABeta) peptides and neurofibrillary tangles of tau proteins, Alzheimer’s disease affects approximately 50 million people globally and is the leading cause of dementia.

Despite its prevalence, academic researchers and the pharmaceutical industry have struggled to develop effective therapies against Alzheimer’s disease, with many drugs failing in late stage clinical trials. Research carried out between 2002 and 2012 concluded that the condition has a 99.6% trial failure rate.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Just this week, Biogen and Eisai announced they were discontinuing the Phase III trials of beta amyloid cleaving enzyme (BACE) inhibitor elenbecestat due to an unfavourable benefit-risk ratio. This was the second of Biogen and Eisai’s drug studies to be discontinued in 2019; the clinical development programme for aducanumab was discontinued in March.

Current challenges in treating Alzheimer’s

As a neurodegenerative disease, Alzheimer’s creates access challenges for researchers seeking to better understand the condition, and thethe blood-brain barrier makes targeting the plaques with pharmaceuticals difficult.

Alzheimer’s disease alsodevelops gradually over time, meaning by the time patients become symptomatic, their disease has progressed to such an extent that it is too late to try and break up these plaques.

This situation, combined with the growing prevalence and healthcare burden of this neurodegenerative condition – the Alzheimer’s Association estimates there will be a 68% increase in global prevalence and burden of dementia by 2050 – has pushed some to consider whether preventative approaches to treatment could be the solution.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe leading approach is a vaccine; despite some candidates facing set-backs early on in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the theory that vaccination could prevent cognitive decline is gaining traction.

One company with a promising vaccine candidate is Switzerland based AC Immune; its therapeutic Abeta vaccine ACI-24 is currently being investigated in Phase Ib and II clinical trials.

Knock back for Elan’s Alzheimer’s vaccine

AC Immune CEO Andrea Pfeifer points out that the failure of Elan and Wyeth’s vaccine candidate – AN-1792 – in the early 2000s due to safety problems is a key factor behind the relative lack of Alzheimer’s vaccine research programmes today.

The Phase II study of the companies’ AN-1792, which targeted Abeta peptide, was abandoned in 2002 after participants developed meningitis and inflammation of the brain.

Although researchers at the two companies identified why AN-1792 triggered inflammation and presented these findings at the Society for Neuroscience in New Orleans, US, allowing others to learn from the failure, Pfeifer states “this incident is still in the head of regulatory agencies” when considering new Alzheimer’s vaccines.

“When we started our vaccine programme, we really had to show over many years to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) that our product is efficient, and also safe.”

Understanding ACI-24’s mechanism of action

Pfeifer explains ACI-24 is developed using AC Immune’s SupraAntigen technology to “anchor antigens on the liposomes”, which are then injected into the patient.

The patient’s body makes antibodies, which are “90% specific to the pathological Abeta protein”, and will not target the normal Abeta peptides, allowing the vaccine to “dissolve plaques or inhibit the formation of plaques”.

Pfeifer continues: “The product was so efficient in mice, it could completely restore the memory in this transgenic mice model.” As well significantly reducing the plaques and restoring memory in pre-clinical models, ACI-24 had a favourable safety profile not linked to local inflammation because it targets the pathological Abeta protein “without activating the inflammatory pathways in the brain and activating T cells.”

Following on from this impressive success in mice, ACI-24 is being investigated in Phase II clinical studies of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s patients.

Pfeifer believes the only way to treat Alzheimer’s is through prevention “early and safely” and that the best way to do this is through vaccination “20, 30, 40 years beforehand”. Looking to the future she explains AC Immune’s “goal is to have one injection per year after initial vaccination” for people at higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

She explains risk could be identified genetically and through biomarkers. An example of a risk gene is apolipoprotein E-e, which has been shown to factor in around a quarter of Alzheimer’s cases. Pfeifer continues the build-up of ”tau [protein] in the brain seems to be a very high risk factor for these people to get the disease”.

Investigating ACI-24 in Down syndrome population

In addition to studying ACI-24 in Alzheimer’s patients, ACI immune are also studying the Abeta vaccine in the Down syndrome population “which was recently identified to have a lot of A beta protein and develop plaques very early in life”. They develop Alzheimer’s-like characteristics at between three and five times the rate of the general population, a phenomenon that for many years went unnoticed due to the high mortality rate of Down syndrome patients. As the prognosis for Down syndrome patients has improved, the Alzheimer’s problem has become more apparent.

“At 20, [people with Down syndrome] have Alzheimer’s signals, at 40 they have all Alzheimer’s symptoms, and at 60 the majority have dementia,” says Pfeifer. “Previously…people with Down syndrome died at 30 or earlier of heart disease, but now these…patients live a normal life and can live to 60 and beyond, [at which point] Alzheimer accumulation becomes a real issue.”

The reason for the close association between Alzheimer’s and Down syndrome is genetic because Chromosome 21, which Down syndrome patients have three copies of, carries the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene. This gene plays a role in the build-up of beta amyloid protein and plaques in the brain, meaning that those with Down syndrome have more production of the beta protein from birth.

Benefitting both Alzheimer’s and Down syndrome patients

Being able to study the vaccine in a “more homogenous environment” based on a genetic marker can help to overcome issues with discovering and developing Alzheimer’s treatments, Pfeifer explains.

In addition to the difficulty with offering treatment before disease onset, these challenges include uncertainty in Alzheimer’s patients about the mechanisms and timing of disease-induced brain changes, genetic and age-related variability and risks of including patients with other forms of dementia with different causes.

Pfeifer hopes ACI-24 can “make a difference in the lives of people with Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s”. She believes, if efficacious and safe, ACI-24 could be administered early in the lives of Down syndrome patients, preventing them from developing dementia; long term treatment with existing Alzheimer’s drugs would be both expensive and “place a burden on the body”.

Initial data from the Phase IB study shows ACI-24 was well tolerated at all doses, with no subjects being withdrawn due to serious adverse events, and a significant anti-Abeta immunoglobulin response being recorded.

Pfeifer wrote in a statement: “These initial interim Phase 1b data support the continued study of ACI-24 in this trial to treat AD-like symptoms in DS as well as in our ongoing Phase 2 trial in subjects with mild AD.

“[There is an] unmet need and the significant opportunity that exists for studying AD-like symptoms in this more homogeneous population, which may yield critical information for the potential benefit of DS subjects as well as the broader AD community.”