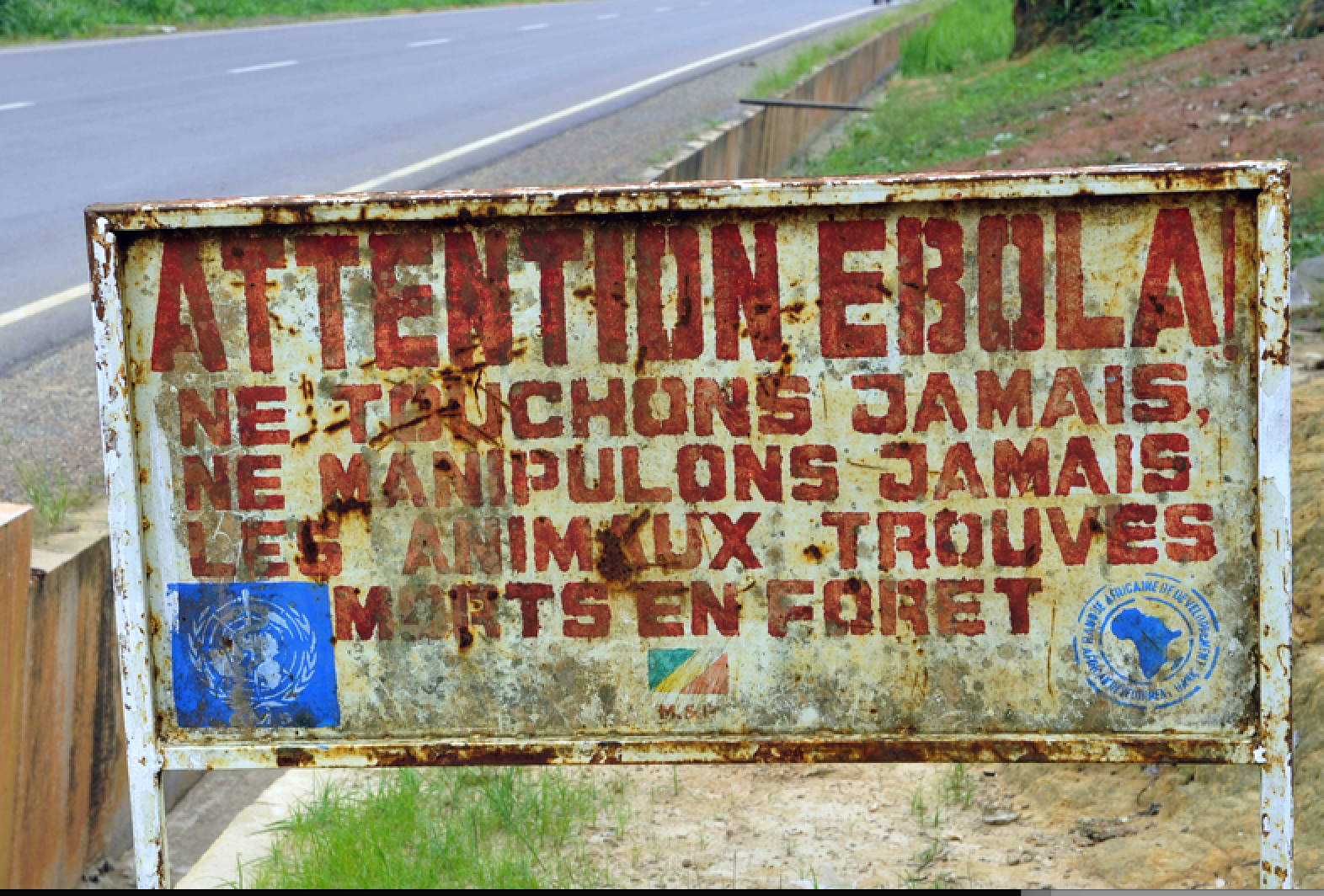

Ebola, described by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) as ‘one of the world’s deadliest diseases’, is currently rampaging across the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This is the second most deadly outbreak of the viral disease in history, and according to MSF it has caused 1,700 deaths since it began in August 2018.

The deadliest outbreak occurred across West Africa between 2014 and 2016; it saw saw 28,616 cases and 11,310 deaths, many of whom were health and aid workers, and represents a 50-70% fatality rate.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

The scale of this outbreak spurred research and development into treatments to help stall the transmission of the condition between humans; this momentum has continued in the current recent outbreak, leading to significantly more effective treatments being developed. However, this begs the question, can drugs and vaccines alone stop Ebola in its tracks in the DRC?

Charting Ebola outbreaks

In late December 2013, Ebola began to spread across Western Africa from an index case of a young child in southern Guinea. By March 2014, samples sent to laboratories for analysis proved that the virus was Ebola and Guinea health officials informed the World Health Organization (WHO) of the outbreak.

Over the next two years, the disease spread across borders to a number of West African countries, including Sierra Leone, Nigeria and Liberia.

Supported by partners including MSF and the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, and international aid, the WHO responded initially by increasing the number of treatment centres to deliver supportive care and symptomatic therapies. This was followed by further interruption and containment of all methods of Ebola transmission.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThese approaches were successful; the end of the outbreak – 42 days, two incubation cycles of the virus, after the last confirmed case – was being declared by the WHO in the affected countries throughout June 2016.

A year on from the 2018 outbreak

Unfortunately, only two years later, in August 2018, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)’s Ministry of Health declared a new outbreak of Ebola in the North Kivu province.

Figures suggest there have been more than 2,600 cases to date, and the lack of epidemic control has caused them to increase at the alarming rate of 80 to 100 per week.

This escalating situation led to the WHO declaring the outbreak a ‘public health emergency of international concern’ in July 2019; there are rising concerns from neighbouring countries about the virus spilling over porous borders.

WHO director-general Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus commented: “It is time for the world to take notice and redouble our efforts. We need to work together in solidarity with the DRC to end this outbreak and build a better health system.

“Extraordinary work has been done for almost a year under the most difficult circumstances. We all owe it to these responders — coming from not just WHO, but also government, partners and communities – to shoulder more of the burden.”

Ebola outbreaks: the pharma response

The scale of the outbreak and the resulting medical emergency spurred researchers and pharma companies to focus on developing vaccines and treatments against the virus.

During the 2014-6 West African outbreak, there was a race to develop the first vaccine for Ebola; Merck brought the first vaccine to market after licensing vesicular stomatitis virus–Zaire Ebola virus (rVSV-ZEBOV) vaccine from the Canadian Public Health Agency. This candidate was funded by the WHO, Wellcome Trust, MSF, as well as the governments of the UK, Canada and Norway.

In a trial carried out in Guinea, there were no Ebola cases recorded 10 days after vaccination for the 5,837 people who received the vaccine. WHO Assistant Director-General for Health Systems and Innovation and the study’s lead author Dr Marie-Paule Kieny said: “While these compelling results come too late for those who lost their lives during West Africa’s Ebola epidemic, they show that when the next Ebola outbreak hits, we will not be defenceless.”

Similarly, towards the end of the 2014-6 outbreak, a clinical trial of an experimental Ebola treatment ZMapp was found to be safe and well-tolerated. However, the drug’s efficacy was not able to be confirmed at the time because there were too few people with the infection to test it on. In the absence of alternative options, the WHO decided that the benefits of the drug outweigh its risks, so the drug is being used in the ongoing DRC outbreak.

Despite the efficacy shown in the initial studies of the Ebola rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine, later trials have shown that it is less effective when not administered immediately; something which is not always possible in unstable, remote settings. The vaccine’s efficacy was also called into question when a vaccinated young woman, as reported by the Guardian, caused the spread of Ebola into a new region – South Kivu.

These settings also pose another serious challenge because both ZMapp and the vaccine need to be stored a certain temperatures; ZMapp requires cold chain for distribution and storage, while the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine must be kept at -70°C.

Developing better treatments for Ebola

Given the scale of the outbreak and the challenges facing existing treatments in curbing it, industry, led by the WHO and the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, sought to investigate new experimental treatments in a multi-country PALM study.

Two of the four antibody-based treatments studied in PALM are now proven to be more effective than ZMapp at treating Ebola; as a result, only these two drugs – mAB114 and REGN-EB3 – will be used to treat Ebola going forward. The other two drugs trialled in the PALM study were ZMapp and remdesivir.

REGN-EB3 manufacturer Regeneron’s senior director of clinical development and experimental sciences Sumathi Sivapalasingam commented: “This trial was conducted in difficult circumstances during a public health emergency, and we appreciate the efforts of the WHO and other experts to add REGN-EB3 to the trial.

“This trial is a remarkable advance in the decades-long struggle to respond to Ebola and we appreciate the tremendous efforts of the many governmental and non-governmental organizations who made it possible.”

Ridgeback Biotherapeutics licensed mAb114 from the US National Insitutes of Health in late 2018. The company’s CEO Wendy Holman commented: “We will continue to concentrate on ensuring that mAb114 is available to respond to the current and any future outbreaks.

“Today’s news from the PALM trial helps to reinvigorate us and keeps us fixated on our mission.”

Talking generally about this breakthrough, MSF advisor for tropical disease Dr Esther Sterk said: “This is very good news for patients. It is good that these two drugs are recommended because not only do we expect them to improve their chances of survival, but they are also easier for medical staff to administer.”

Importantly, these breakthroughs have not led to complacency in the pharma community; research for and studies of more treatments for this life-threatening virus are ongoing. For example, Janssen’s Ad26.ZEBOV and Bavarian Nordic’s MVA_BN-Filo vaccines are being trialled in Uganda, which neighbours the DRC and has experienced previous outbreaks of Ebola.

Remaining challenges to ending the outbreak

Unfortunately, new drugs alone cannot control the outbreak. Unlike the 2014-6 outbreak, the current Ebola epidemic in the DRC is occurring in a deadly conflict zone.

This has caused a mistrust of the government, sometimes leading to violence against international healthcare workers, and a reluctance to be vaccinated; Stat News reports it is common for the local community to hide its sick from outsiders and seek to care for people locally.

MSF’s deputy coordinator of the Ebola response in the DRC Trish Newport explained: “One of the biggest problems with the outbreak is that this Ebola response has never gained the trust of local people.

“This is because the outbreak is happening in an area that has been plagued in recent years by conflict and massacres of civilians.

“If the population doesn’t trust the response, the tools will never be able to be used to their full potential.”