Cell and gene therapies (CGTs) are a relatively new class of treatments with revolutionary potential for a number of hard-to-treat diseases. Investment in the space has grown exponentially in recent years, but these products come at a price – just 11 of these therapies approaching approval will cost the US health system around $15bn to $45bn by the end of 2024.

ICON’s global business lead for CGTs Tamie Joeckel speaks to Pharmaceutical Technology about overcoming the roadblocks to affordability for these advanced treatments.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Darcy Jimenez: What makes cell and gene therapies so expensive?

Tamie Joeckel: Cell and gene therapy is a new frontier of medicine with few standards. The complexities of these therapies are part of what I call the “journeys” – the regulatory journey, site journey, product journey and patient journey. Each present requirements and components that contribute to the expense.

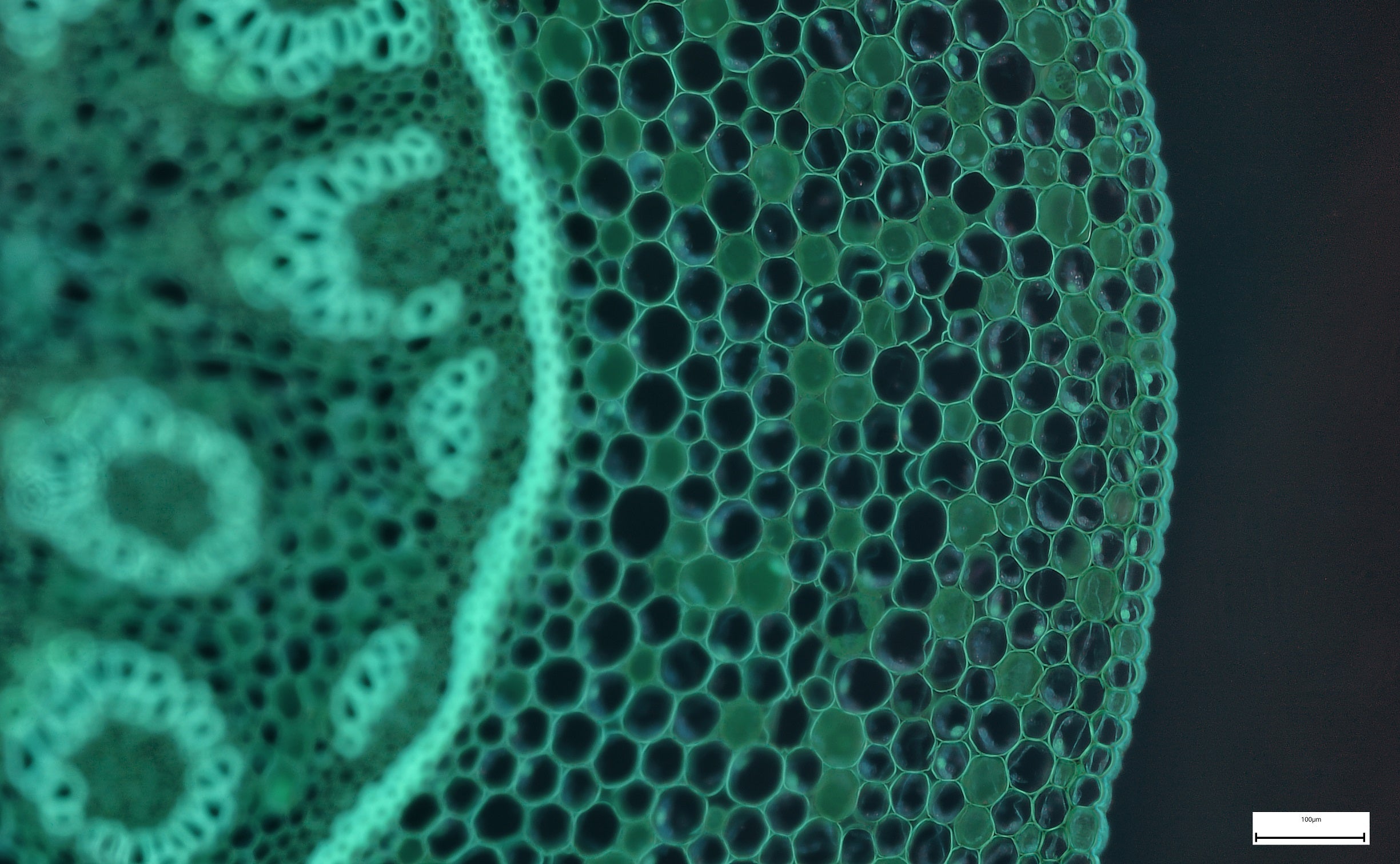

Within the product journey, the manufacturing process is probably one of the primary contributors because you’re working with ‘living therapies’. Take, for instance, an autologous programme – where you’re using the patient’s own cells to manufacture a batch of one dose that goes back to the patient. Manufacturing capacity is a primary constraint in these programmes, especially as you try to scale up. It’s difficult enough manufacturing for a few hundred patients in clinical trials – imagine when the therapy is commercialised with potentially thousands? Even with the movement toward allogeneic, multi-dose therapies made from healthy donor cells, where multiple doses are manufactured, it’s still a very complex manufacturing process that can take several weeks. Single source raw materials only exacerbate the issues.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe overarching supply chain requirements for handling and moving living therapies that can be both time and temperature-sensitive adds additional costs in equipment, overnight transportation, ultra-cold storage and ‘white-glove’ handling to ensure both product and patient safety.

The patient journey can add considerable expense when we’re talking about scaling these therapies to treat thousands of patients rather than hundreds of patients. Patient concierge services can include airfare and hotel for patients and caretakers if treatment is centralised to a few sites. We have several rare disease programmes where patients are flown to a single site for treatment. In addition, many of these therapies require hospitalisation and/or daily follow-ups for an extended period of time. The sites involved in the therapies usually require specialised equipment and ongoing training.

Some of these therapies have regulatory requirements of long-term follow-up (LTFU) with patients up to 15 years. These registries and reporting requirements certainly add expense overall.

DJ: How does the cost of cell and gene therapies present a challenge to their widespread adoption?

TJ: CGT therapies can address the root cause of disease versus just treating the symptoms. Sometimes curative, they are administered as either a single dose or a handful of doses compared with conventional medicine. Our fee-for-service reimbursement models with payers are built around chronic treatments for these diseases, while CGT therapies can be a single treatment that costs anywhere from half a million dollars to millions of dollars for a dose. Our payer reimbursement systems are really not set up for that level of therapy cost.

Payer systems can have projected budgets based on historical data that doesn’t include these new types of treatments. For instance, let’s take a rare disease like haemophilia. A single payer may have hundreds – or even thousands – of patients that have the disease, where the average annual cost of prophylactic treatment is $100,000 per year. If you have 300 patients on your plan, that’s $30 million per year projected cost. How does the payer handle the fact that all of a sudden, this bolus of patient population has now qualified and wants access to a million-dollar therapy? This is the reason we’re working with regulatory and payer groups on creative reimbursement models that are outcomes- and value-based, that may include shared risk from the sponsors.

Think about it – by 2025, the FDA expects to approve 10 to 20 cell and gene therapies a year, standing to benefit an estimated 500,000 US patients by 2030. That certainly highlights the need for innovative, risk-sharing and value-based payment models.

DJ: How can drug companies streamline or optimise the drug discovery and development processes for these therapies?

TJ: As we talked about in the very beginning, this is a new frontier of medicine and there are few standards that exist in this space. It’s an ongoing pursuit, an ongoing conversation in the CGT sector. Standards in biologics aren’t easy. There’s no such thing as a ‘standard cell’.

But there is a lot of work that’s going on in various groups discussing harmonisation of best practices, standardisation, and actually looking at how we might be able to share information across the board, so that we can eliminate as many costs as possible. To be honest, there’s more sharing happening in academia than in the commercialisation phases in CGT.

Best practices and standardisation are also needed in the clinical trial phase of these therapies. Highly desirable sites are being charged with running multiple protocols that each have their own nuances and requirements. The more streamlined and harmonised we can get on how these trials are run, the easier it is on these sites and it allows them to handle more protocols.

Another recommendation for sponsors is early and frequent interactions with health authorities to support alignment and streamlining the CGT development journey. You don’t have to wait to communicate with the FDA in a pre-IND meeting. For innovative, investigational products like CGTs, there an option for an informal, non-binding, one-time consultation with Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. This meeting focuses on product characterisation, early proof of concept studies and chemistry, manufacturing and controls challenges.

An ongoing challenge in CGT is the ever-changing regulatory landscape that varies from country to country, sometimes down to a regional level.

DJ: Health technology assessment agencies are now asking for 15 years of follow-up data on some CGTs. How does this further complicate efforts to encourage adoption of these treatments, and what can drug companies do to plan around this?

TJ: When we’re planning trials, we typically will take the patient registry and long-term follow up as a separate protocol. As far as planning, it’s quite complex and variable. We must consider characteristics of the clinical trial patient population, duration of the LTFU observations, data collection and reporting.

In the US with multiple payers, tracking patients over a 15-year period can be quite challenging. We have to track patients as they change jobs or move from one insurance company to another. When planning these programs, LTFU planning is part of any new study operations. We consider ongoing and frequent data reconciliation along with flexible resourcing models that can be ramped up or down as needed. CGT products that integrate vectors and genome-editing products may require additional monitoring. A key part of the planning process is addressing the challenges in data migration from main studies to the long-term study. Fortunately, we have great teams who assist in the planning and execution.

DJ: How can drug companies encourage health systems to adopt CGTs?

TJ: Consistent evidence on the health benefits of a new therapy is not only needed to justify regulatory licensing, but also health insurance coverage and reimbursement. Certainly, the monitoring of the LTFU data can support the required analysis.

Real-world evidence (RWE) derived from real-world data can strengthen regulatory submissions, and it’s important to plan for RWE before, during and after participation in a programme. The biggest piece of advice is to plan, plan, plan, and build bridges between quality, clinical and non-clinical stakeholders. Develop a regulatory strategy as soon as development begins and analyse the landscape to determine the best market access model. As mentioned above, meet with regulators early and often to incorporate insights into the programme.

Your regulatory strategy should evolve along with development as new information about the competitive environment, study results and interactions with regulatory agencies proceed. Demonstrating both clinical and economic evidence to providers, healthcare decision makers and, most importantly, payers is key.

CGT is a new frontier in medicine and navigating these complexities are challenging. But with proper strategic planning, sponsors can clear the obstacles and bring the ground-breaking, curative therapies to patients.

DJ: What other steps must be taken to boost investment in CGTs? Can this be incentivised?

TJ: Globally, there are over 1200 regenerative medicine clinical trials underway and nearly 1100 developers active in the sector. It is a new frontier, but I think that the promise of potentially curative therapies, especially in disease states with unmet needs, speaks for itself. The fact that you might have a curative of chronic rare diseases, or a curative of potentially terminal diseases, is significant.

Certainly, the price point of these therapies is something of a delimiter. But when you look at the investment environment, and the record-breaking investments that have been made in cell and gene therapy over the last few years, all we’re seeing is increased momentum and interest in moving this particular space forward. According to the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine, in 2020, the sector raised a record $19.9bn and in the first six months of 2021, we’ve already reached over $14bn. The global CGT market is on pace for annual records in both approvals and financings. It’s a healthy market.

Cell & Gene Therapy Coverage on Pharmaceutical Technology supported by Cytiva.

Editorial content is independently produced and follows the highest standards of journalistic integrity. Topic sponsors are not involved in the creation of editorial content.