It’s widely known in the industry that private investment in biotech and biopharma has been down in recent years. Whilst there was an uptick in biotech and biopharma funding in 2024, this was primarily in early-stage companies, meaning those who missed out during the funding drought continue to be left behind.

In lieu of private funding, biotech and biopharma fell back on government-led funding schemes. However, some of these schemes have been paused or slashed amid global political changes.

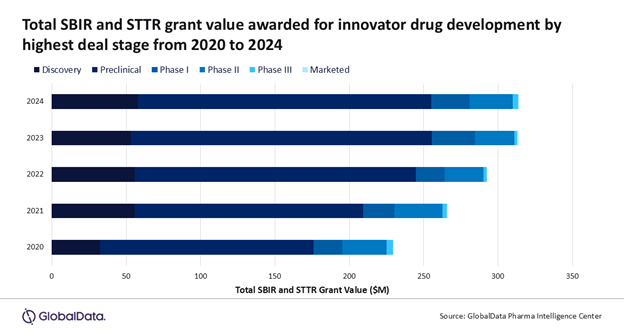

Following the inauguration of US President Donald Trump, there has been a series of directives targeting the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The entity is the largest global funder of biomedical research, providing federal government funding to US-based early-stage companies, with more than $1.4bn in NIH Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) grants involving innovator drugs awarded between 2020 and 2024, according to GlobalData.

GlobalData is the parent company of Pharmaceutical Technology.

Meanwhile, two European Union (EU) funded programmes that partially support biotechs and biopharma with their pipeline development have also faced cuts. EU4Health funds faced a 20% drop with funds diverted to Ukraine, and the Horizon Europe project also took a €2.1bn ($2.28bn) cut. At the same time, the French Government has passed the French Social Security Finance Bill (PLFSS) & Medicines, which will impact government investment into biotechs.

Change is happening

The funding drought came due to overinvestment in 2021, says Michelle Hoffman, CEO of the Chicago Biotech Consortium (CBC). According to Hoffman, CBC – which supports preclinical companies move into the clinic – is seeing the impact of the financing lull.

“I think we have slowed down at least by 50% and that’s a huge thing in a place like Illinois. We are going to have fewer drugs enter the clinic and those that do make it are on a shoestring package,” says Hoffman.

While change has been predicted by the industry, a cut of government funding was not expected, adds Ali Pashazadeh, founder of Treehill Partners, a strategic and financial advisory company for healthcare.

“One thing we have been predicting for the past three or four years is that the drought that we have in funding from IPOs and other investor funding would remain dry for quite a period of time, which has been the case,” Pashazadeh explains.

“What we didn’t predict was the governmental funding drying up when it comes to general research. Treehill has never been clear on why the governmental funding exists or what it’s trying to achieve and what the accountability metrics are.”

Government funding should not be the sole income

Government funding is used heavily by early-stage companies to get off the ground. Once they are established and therapies show signs of efficacy, they could start gaining interest from private investors of venture capital (VC).

“Without government funding, you’re not going to have the foundational research that’s necessary to build the next generation of therapies. While I don’t see the industry feeling this in the next couple of years with extreme pain. I think what you’re going to be seeing is the tail end of this for a very long time, over the next decade,” Hoffman explains.

UK BioIndustry Association (BIA) CEO Steve Bates OBE said that government-led funding should not be the only source through the pipeline process.

“What we are keen to do is make sure there is a continuum of funding,” Bates says. “As trials get larger, the cost of running them increases but equally, the risk profile of those later trials goes. While the quantum of cash needed is higher, the risk profile of investing is lower.”

Pashazadeh says the cuts could benefit the industry in some ways, by making companies run more efficient studies: “I think it’s a welcome change that the industry is looking at the efficiency of governmental funding of basic research. It’s unfortunate but I do think something needed to change.”

Oury Chetboun, CEO of French biotech Seekyo, utilises several national schemes such as the French Bank of Innovation (BPI) and research tax credits.

He says: “If you are an early-stage and innovative company, at the end of the year, you can claim 30% back from the French government for overall expenses related to research. That’s a very interesting and attractive tool.” Chetboun adds that due to clinical trials being part of the R&D process, they would be eligible.

Alternative trial designs could help

Companies are looking to use alternative trial designs which allow early-stage therapies to be investigated in several indications in just one protocol, reducing the cost.

“We’re using alternative trials, such as umbrella and basket trials so we can enrol across different types of indications,” says Chetboun.

“In our case, it’s a good thing because our lead compound can apply to several indications. If we do that in an umbrella trial and have four different indications then at the end of the Phase I maximum tolerated dose portion, we can choose an expansion phase in a certain indication.”

Pashazadeh says that the issue is not due to traditional trial models but a trial’s purpose. Treehill ran research that found certain Phase II and III studies “had no scientific or commercial utility”.

The Treehill Partners founder added: “We were shocked that a global CRO would work with a biotech spend all that money and design a study, but they weren’t sure what product they were launching. I don’t think companies need to be running innovative study designs, it’s about doing genuine drug development that is needed for progression. By doing that, companies can also generate more return for investors.”

How the impact will be felt down the line

According to Hoffman, this lack of funding on both the private and public side in the early stage biotech and biopharma will likely translate into a lack of assets for big pharma venture arms to acquire through M&A.

“There’s been a lot more reluctance to invest in early-stage assets so that means organisations like us or other mechanisms are the only source to get early-stage ideas to the spot where pharma’s want to take them on. I think pharma is going to feel that pain, not really in the next year or two but once therapies with clinical proof of efficacy are run dry, there will be a noticeable gap.”

This, coupled with biotechs having reorganised pipelines or stopping operations altogether, could further translate into a lack of therapies making it to the market says Hoffman.

Hoffman adds: “The rates of FDA approvals, there is a ten-year lead time so something happening a decade before will influence what FDA does a decade later, and I think that’s what we are going to see.”

Bates says that pharma already seems keen to restock their pipelines but acknowledges there could be a gap.

“What we are seeing is that pharma is keen to restock their pipelines and are acquiring assets from biotechs once again,” emphasises Bates.

“There is always whittling down as therapies go through the development process, and whether that is narrowed slightly at different points as a result of the funding, that has probably been the case, and it could be that some things are delayed that could otherwise have moved faster.”