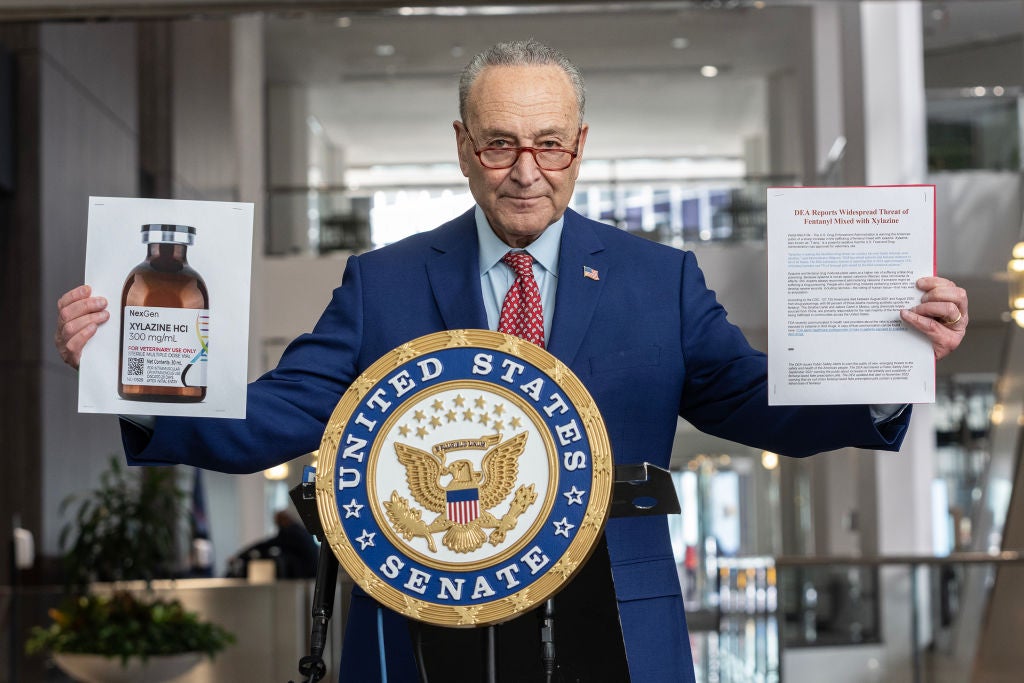

In February, the FDA issued an alert restricting the import of the veterinary sedative xylazine or tranq and the ingredients used to make the drug. This followed in the wake of a Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) Joint Intelligence Report in October 2022, which stated that xylazine is widely available from Chinese suppliers on the internet.

According to a June 2022 study, xylazine has been detected in the illicit drug supply in 36 US States, and the DEA has reported that approximately 30% of the fentanyl seized by the Agency contained xylazine. The drug is sold under the street names tranq, tranq dope, sleep-cut, and Philly dope, and has become inextricably linked to the current opioid crisis.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

“Xylazine started showing up in the dope in Philadelphia around 2010 and recently started to spread across the US, says Jon Zibbell, PhD, a senior public health scientist at RTI International, a non-profit research institute in North Carolina that provides data and analysis to inform public policy.” Zibbell says that similar to how fentanyl was first used to turbocharge a weakened heroin product, people may be using xylazine to extend fentanyl’s extremely short high. Because the high from fentanyl lasts mere minutes, xylazine may be a cheap and readily available way to give fentanyl the “legs” that opioid users want, he adds.

Zibbell adds that most people who use opioids prefer the semi-synthetic types, like oxycodone and heroin, because both provide a lengthy, euphoric effect. But this is not the case with fentanyl. Opioid users regularly complain about fentanyl’s short high and the need to use more frequently to maintain the opioid effect, but insist they have no other choice because they are physically dependent and terrified of fentanyl withdrawal.

Fact box: What is tranq?

- Tranq or xylazine is an alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist: a non-opiate sedative, muscle relaxant, and analgesic, which the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authorised only for veterinary use.

- In humans it can cause respiratory depression, hypotension, bradycardia, hypothermia, miosis, and high blood glucose levels. Xylazine is also associated with necrotic and expansive skin ulcers which, if left untreated, can progress to gangrenous wounds that may require the amputation of limbs.

- Xylazine and fentanyl can induce an ‘atypical overdose’ and render a person unresponsive to naloxone, the go-to medication designed to rapidly reverse opioid overdose.

“[Xylazine’s] creating what we refer to as atypical overdoses,” says Zibbell, “meaning they don’t follow the same pattern as an opioid-induced overdose. For example, we are seeing people who become unresponsive, but are still breathing.” Due to the unresponsiveness to naloxone, the only available response to overdoses are tactics to keep people breathing and putting them in the recovery position so they don’t choke on vomit, etc, he adds.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataXylazine test strips

Test strips that detect fentanyl, and more recently xylazine, in urine are proving to be an effective tool for harm-reduction organisations.

“It makes sense to have a xylazine strip so you can check to see if your dope contains xylazine,” he says. “The research on fentanyl test strips shows that people will use them when they perceive themselves at risk, and then practise safer consumption behaviours to reduce risk and increase locus of control.”

However, there are issues that need to be addressed. For example, xylazine test strips are expensive. As per Stat News, the Canadian company BTNX plans to sell xylazine strips at $200 for a box of 100 strips. “To get a good deal, health organisations are needing to buy them in bulk, making cost a barrier to access,” says Zibbell.

There is also the possibility of false-positive results when methamphetamine and related substances are present.

“We found that more water is needed to dilute the meth-based solution in order for the fentanyl test strip to work effectively,” explains Zibbell. “Interactions with other substances and the chance of false positives related to sample dilution are things to consider with xylazine strips moving forward.”

Regulations on importation and domestic use

In the backdrop of recent deaths due to xylazine, the DEA is regulating the legal, domestic supply of the drug that health analysts believe will prove more important in preventing illicit use. There have been calls to make xylazine a scheduled drug in the US, but so far only three states have classified it as a controlled substance. Florida made it a Schedule I drug in 2016, West Virginia has since made it a Schedule IV substance, and Ohio has classified xylazine as Schedule III. In March of this year, a bill sponsored by a bipartisan group of U.S. senators and representatives, named the Combating Illicit Xylazine Act, called for urgent action at a national level.

“If the xylazine used to adulterate America’s fentanyl supply is domestically sourced, then scheduling it will provide the ability to track supply and restrict access,” says Zibbell, “but that doesn’t mean the problem goes away. There will undoubtedly be other novel and similar substances coming down the pike.”

Indeed, medetomidine, another synthetic veterinary sedative is already being detected in the US drug supply, most recently in Maryland.

Synthetic drug crisis

Zibbell believes that the torrent of novel and designer substances in the fentanyl supply, amid sharp declines in oxycodone and heroin, suggests the US may be witnessing a mounting “synthetic drug crisis”:

“DEA seizures of heroin have plummeted over the past five years. What we’ve been seeing are fentanyl analogs, novel benzimidazole opioids, and a growing number of alpha-2 agonists in the illicit fentanyl supply and then people using cocaine and methamphetamine to offset the heavy sedative effects.”

In this “synthetic drug crisis” it’s no longer the unsafe behaviour of substance-dependent people that presents the biggest threat to public health (e.g. injecting behaviour and the spread of bloodborne infections), it’s an increasingly toxic drug supply that includes myriad substances never intended for human consumption.

“An increasingly toxic drug supply is what’s driving the harm,” says Zibbell. “How do we reduce drug-related harm when a toxic drug supply is to blame and not drug use behaviour or unhygienic environments per se? That’s the question that regulators and health organisations are trying to figure out right now.”