Mononucleosis, often abbreviated to mono, is a common viral infection that affects hundreds of thousands of people each year. Generally caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) – itself one of the most common human viruses in the world – the condition may result in a sore throat, fever and severe fatigue.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

According to the British Medical Journal (BMJ), around 50 to 100 people out of every 100,000 are affected annually, with a skew towards adolescents and young adults. One English study found that, by the age of 35-40, some 90% of the population had antibodies against EBV.

This did not mean that they’d all suffered from mono. Most people who contract EBV will never show any symptoms, particularly if transmission occurred during childhood. However, if the virus is contracted during adolescence, many do develop mono (the Centers for Disease Control estimates 35%-50%). Typically, this is far from a pleasant ride.

While symptoms generally improve within two to four weeks, a significant proportion of patients experience persistent fatigue. A 2009 study, published in Pediatrics, found that approximately 10% of adolescents diagnosed with mono still had symptoms six to 12 months later.

Most concerningly, mono infection has been implicated as a potential trigger for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), an ongoing and somewhat mysterious disorder that can severely impair a person’s quality of life.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataIt may therefore seem surprising that mono is not better understood. The condition has no cure and no vaccine, and the possible links with CFS remain underexplored. Similarly, diagnosis is not always clear-cut, owing to the similarities with strep throat.

Diagnostic hurdles

Dr Mark Ebell, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Georgia, has been interested in mono since the 1990s, when he first reviewed the research in the field. At the time, he was struck both by the prevalence of the condition and the lack of available information.

Two decades on, he wanted to see how times had changed. Together with colleagues in the department of epidemiology and biostatistics, he compiled a systematic review of studies involving the clinical diagnosis of mono. This was published in The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in April 2016.

“I have been doing a series of systematic reviews of the diagnosis of common respiratory conditions, including sinusitis, pharyngitis, and influenza,” Ebell explains. “We actually don’t know how often the diagnosis of mono is missed.”

The issue with misdiagnosis is that it may lead doctors to prescribe antibiotics, which are useless against viral infections. This not only fails to help the individual patient – it ties into the growing problem of antibiotic resistance.

Ebell’s review, which included 11 studies into mono detection, found some clear markers that set the condition apart from its differential diagnoses.

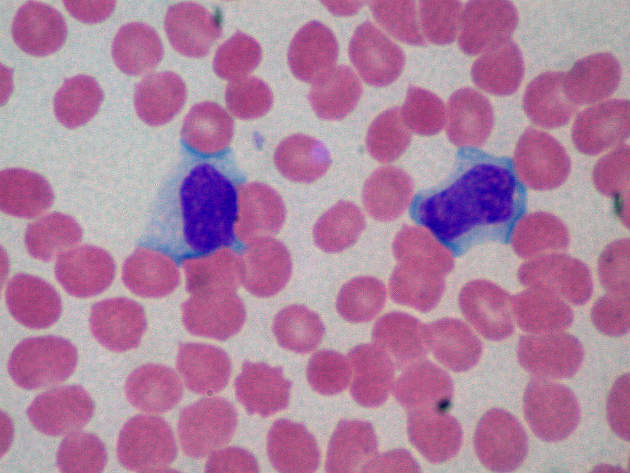

“The signs and symptoms that best rule in infectious mononucleosis are posterior cervical, inguinal, or axillary adenopathy or the presence of splenomegaly or palatine petechiae, while the absence of any lymphadenopathy makes it unlikely,” he explains. “A high percentage of lymphocytes, and especially atypical lymphocytes, strongly rules in mononucleosis.”

Most of the time, mono is diagnosed purely through an assessment of the symptoms, which is later confirmed with a serological test that checks for lymphocytes. Ebell feels that diagnostic procedures could be improved.

“We need a prospective study of patients with suspected infectious mononucleosis who all get a high quality reference standard test, and then use that data to develop and validate a clinical decision rule that can classify patients as low, moderate or high risk,” he says.

Treatment and drug development

But diagnosis is only one piece of the puzzle. Mono patients must also contend with a lack of treatment options, with doctors typically prescribing rest and fluids as opposed to any particular drug. Although painkillers may be useful in alleviating symptoms, along with the corticosteroid Prednisone, received wisdom accepts the illness needs to run its course.

Clearly, this situation is not ideal, particularly given the possibility of persistent symptoms and the fact that EBV is implicated in certain cancers. So what is being done to develop a vaccine or cure?

EBV is classed as a herpesvirus, along with the viruses that cause herpes simplex and shingles. It has been suggested that valacyclovir, an antiviral used to manage other herpes-associated infections, might also be of use for EBV. A number of studies have found benefits, with some noting that valacyclovir might also be used to treat CFS in cases where EBV infection has occurred.

However, antivirals are not recommended as a first line of defence. One study found that, while valacyclovir might help decrease oral viral shedding (therefore making mono harder to spread), it didn’t improve the clinical symptoms.

Recently, a more promising contender has emerged: the well-established drug spironolactone. Ordinarily used to treat heart failure, this diuretic also appears to be capable of blocking viral infection.

“We have found a new therapeutic target for herpesviruses. We think it can be developed it into a new class of antiviral drugs to help overcome the problem of drug resistant infections,” said lead author Sankar Swaminathan, from the University of Utah, whose findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) in March 2016.

Vaccinations

According to researchers at the University of Minnesota Medical School, writing in the journal Clinical & Translational Immunology in 2015, developing an EBV vaccine ought to take priority for researchers. This would not only have the potential to prevent mononucleosis; it might also offer some protection against multiple sclerosis and Hodgkin lymphoma.

They pointed out, however, that while an EBV vaccine was first proposed in 1973, progress has been “painfully slow”. To date, just two vaccine contenders have been tested in humans, neither with much success. EBV gp350, the more promising of the two, has been tested out in a single phase II clinical trial. This found a reduction in the rate of mono, but no reduction in EBV infection.

More recently, researchers from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) developed an experimental, nanoparticle-based vaccine that targets the same protein more precisely. In mice studies, this investigational vaccine induced as many as 100 times more antibodies than previous vaccine designs.

Clearly, more work needs to be done, both in terms of developing a vaccine for EBV and in treating mono. Because mono has long been viewed as a normal illness of youth, perhaps its very prevalence has stymied research efforts.

Luckily, it appears the tide is turning, with mono no longer regarded as an innocuous condition that does not merit medical intervention. With research continuing apace, this could spell good news for the millions of people infected – and the thousands more who ultimately suffer complications.