High cholesterol is a major problem in the developed world. One of the leading causes of heart disease – and responsible for some 2.6 million deaths globally every year – it affects around 40% of adults worldwide. What’s more, only a small proportion of those affected succeed in keeping their cholesterol levels under control.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

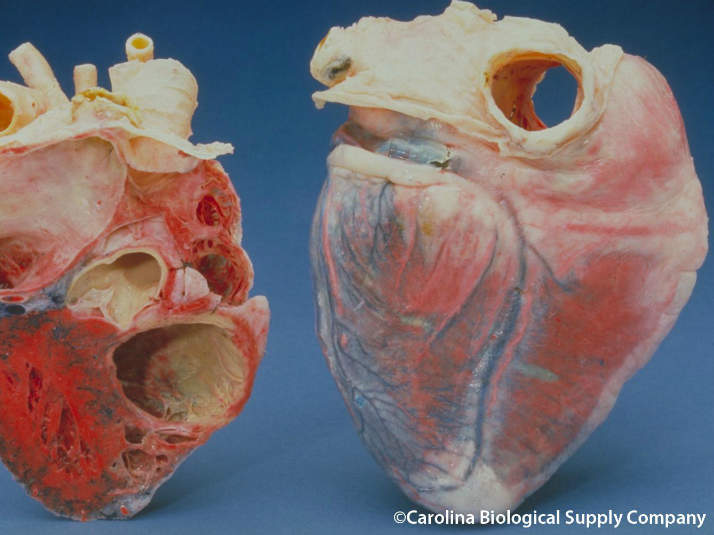

At present, the most commonly prescribed treatment is statins. Combined with exercise and a healthy diet, statins help to lower levels of LDL (‘bad’) cholesterol in the blood, often by around 25%-30%. They do this by blocking the HMG-CoA reductase enzyme in the liver, which in turn slows down the cholesterol production process and reduces the risk of atherosclerosis (the build-up of fatty material inside arteries).

Unfortunately, statins are not effective for everybody, and some people cannot tolerate the necessary doses. What’s more, since their efficacy relies very much on the patient remembering to take them – not easy for those who aren’t experiencing symptoms – their full benefits may not always be evinced.

However, there may soon be an alternative option on the cards. The Medicine Company’s inclirisan, which will soon start phase III clinical testing, has been shown to ‘switch off’ one of the genes responsible for high cholesterol. In the phase II trial (ORION-1), participants’ LDL cholesterol levels dropped by around half.

Moreover, there are no observed side effects, and because the drug is administered via periodic injections, there are no potential issues with adherence.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData“Unlike statins and monoclonal antibodies, this technique takes out the variability due to patient compliance,” says Kausik Ray, professor in public health at Imperial College London and the lead author of the study. “We believe this would be a twice a year injection, that gives you a more than 50% reduction in LDL cholesterol on top of usual care.”

Determining the dose

The ORION-1 study involved 501 participants across five countries, all of whom had high cholesterol and a high risk of cardiovascular disease. Nearly three-quarters of these patients were already taking statins, considered the first line of defence against high cholesterol.

Because phase II studies look to establish the appropriate dosing regimen, patients were administered different doses of the drug (or placebo) via subcutaneous injection, either as a one-off treatment or via two treatments three months apart. They were followed up regularly to assess the effect on their blood cholesterol level.

The patients who received the 300mg dose (as opposed to 200mg or 500mg) fared best – their cholesterol levels dropped by up to 51% after one month, and were still up to 42% lower after six months. If they had received a top-up dose after three months, the six-month reduction was 53%. Notably, all the patients in the inclirisan group responded to the therapy, and these effects were still being felt eight months in.

While the researchers have not quite finished collecting data (they want to check participants’ cholesterol levels after a year), the eight-month data has stoked great interest. These findings – which were published in the New England Journal of Medicine and presented at the American College of Cardiology’s meeting in March – suggest inclirisan could have an important future in cardiovascular care.

“The regimen we envisage is three injections in the first year – the first injection at day one, the second at three months and the next one at nine months,” says Ray. “Then the next ones are six months after that, and six months after that, so from year two onwards it’ll be two injections a year. The way you’d do that is to make sure the patient comes to the doctor’s surgery for their injection, almost like an immunisation regime.”

How it works

Despite its efficacy, the researchers don’t envisage this drug replacing statins. Because inclirisan targets a different biological pathway, patients would ideally take both, giving them a greater cholesterol reduction overall.

“At the top dose, inclirisan gives you a similar percent reduction on top of statins that statins give you compared to placebo,” says Ray. “It is useful for people who, despite statins, have a high cardiovascular risk. At the moment they have to take monoclonal antibodies, which are quite expensive and require injections every two weeks or once a month. Inclirisan has a low injection burden by contrast.”

Like the monoclonal antibodies, inclirisan targets the protein PCSK9. However, it does so at a slightly deeper level, by affecting the genes responsible for the protein’s production.

“There is whole bunch of animal pre-clinical data suggesting this protein is really important to controlling the LDL receptor in the liver,” says Ray. “There are two ways of trying to control it therapeutically – one is the current method, which is using a monoclonal antibody to mop up circulating pieces of PCSK9 in the blood. An alternative approach is to shut down its production in the liver, which inclirisan does via a technique called RNA interference.”

Once the drug is taken up by the liver, it binds to the RNA silencing complex for PCSK9, where it keeps switching off more and more messenger RNA. This means that the effects are felt quickly, and that they persist for a long time.

True primary prevention

As they move into phase III, the researchers are looking to find out whether these reductions in cholesterol translate into a lower incidence of heart attacks and strokes.

“I’m leading this cardiovascular outcome study, which will enrol about 14,000 people with established vascular disease or who have high cholesterol despite taking the highest tolerable dose of statins,” says Ray. “If the treatment is safe, and continues to show what we’ve seen so far, we’d expect The Medicine Company to file for a LDL-lowering license in about three years and a cardiovascular event reduction license in four or five years.”

The drug’s passage to the clinic, then, is unlikely to be especially quick – but it will probably make an impact once it gets there. According to Ray, its main benefit is not that it works better than other treatments, but that it works far more consistently.

“The biggest problem with all the treatments we’ve got at the moment is the patient,” he says. “Even with the monoclonals, which are highly effective, only about 60% of patients are complying with the drug regimen as they should be, meaning their levels of LDL cholesterol return to where they were before. This approach is a very different way of treating cardiovascular disease, but it takes care of a huge unmet need which is the variability and the compliance issues.”

He adds that, because the benefits of a single dose are so enduring, it could ultimately be an incredible treatment for impoverished parts of the world.

“We could go out to the villages, identify people at high cardiovascular risk, and give them an annual injection that would give them a 30% reduction in their LDL cholesterol,” he says. “We don’t know what the cost of the product is going to be, but if the drug is appropriately priced, this could be an exciting option.”

While many questions remain unanswered, the prospects for inclirisan look bright, with the drug holding promise for millions of people.

“It gives you true primary prevention, as opposed to putting the onus on the patient,” says Ray. “So it’s quite incredible when you think about it.”