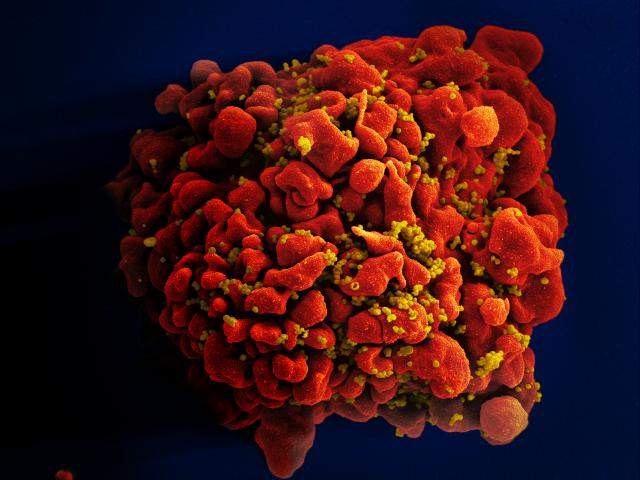

Existing HIV therapies are extremely effective at reducing the amount of virus in the blood and tissue of patients. But there’s one problem. As soon as treatment stops, the virus immediately returns to extremely high levels.

A new approach being developed at the Scripps Research Institute (TSRI), which attacks the HIV virus from a completely different angle to conventional therapies, has proven that there could be another way.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Instead of taking the accepted ‘shock and kill’ approach, which works on the principle that if you activate the cells, the immune system can see them and kill them off, it ‘blocks and locks’ the virus.

“Our drug [a derivative of a natural compound called didehydro-Cortistatin A (dCA)] shuts off very profoundly the transcription from those cells that are infected,” explains TSRI associate professor Susana Valente, lead author of the study, which was published online in October in the journal Cell Reports.

“The block is so strong that over time, even if you remove the drugs, there is not an immediate viral rebound.”

Valente likens it to taking the gas out of a car. “Because it’s sitting there and not being used, the engine becomes rusty,” she says. “So even if you do put gas in, it doesn’t work straight away.”

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataProof of concept for a functional cure

Valente’s research has so far proven that when combining this novel compound – which blocks replication in HIV-infected cells by inhibiting the viral transcriptional activator Tat – with the standard cocktail of antiretrovirals used to suppress infection in humanised mouse models, there is a drastic reduction in virus RNA present. “It is really the proof-of-concept for a ‘functional cure’,” she says.

Once the combined treatment regimen was halted, viral rebound was delayed by up to 19 days, compared with just seven days in mouse models receiving only antiretroviral treatment. And even though the study used the maximum tolerable dose of the drug, there were virtually no side effects.

Valente was also keen to point out that the animal models were exposed to only a month of treatment. The hope is that longer treatment will result in longer, or even permanent, rebound delays.

“We’ve already investigated this in vitro and the longer you treat, the better it gets. We currently have a cell line model where we haven’t been giving drugs for 300 days and there’s no viral rebound,” she says. “Once you go past a certain threshold, it’s very hard to reactivate the cells again.”

The team is currently working to understand what this threshold is. “Maybe we’ll be able to treat a patient for a year and they can have year off without treatment because we know the virus is going to be very, very repressed,” she speculates. “It’s all about the time of treatment versus the time of suppression – those are the questions that are still outstanding.”

Overcoming scepticism

The biggest challenge Valente and her colleagues have faced during the development of their first-of-its-kind approach is scepticism from across the industry.

“The mainstream idea of HIV treatment is the opposite to what we’re doing. Rather than activating the cells so that the immune system sees them and kills them, we are putting the virus profoundly to sleep; we’re basically putting it in a coma,” she explains. “So we’ve faced a lot of scepticism that this is a viable alternative.”

Slowly but surely, though, the industry is acknowledging the potential of Valente’s concept. “Right now, the field has accepted that maybe we can shock and kill certain cells that are easy to reactivate and put the rest to sleep, in a combination type approach,” she says. “Things are moving now and people are accepting this idea more and more. There is even funding from the NIH for these types of approaches.”

At the TSRI, funds are exactly what’s required. “When you’re in an academic lab there’s only so much you can do; you reach a point where you need to do toxicology tests and clinical trials and that’s when you need a lot more money,” Valente explains. “We are at that crossroads now – we’re shopping for companies that might be interested in helping us.”

Lightening the load

If it does eventually get FDA approval, there are several different ways the drug could be used on the front line. First, it could be added to current therapies as soon as a person knows they are infected. “We’ve shown that in combination, it has an additive effect – the faster you shut down the virus, the smaller the reservoir of cells that remain infected is, so the immune system can better control it,” Valente says.

The drug could also be added to the treatment regime of people already using antiretroviral therapy. Valente explains: “Not only would you see a benefit because you’d reduce the viral RNA production in tissues, you’d also reduce the activity of the protein Tat, which is one of the most toxic proteins the virus carries around.”

Eventually, there is also potential for the compound to be used as a monotherapy, significantly lightening the load of the therapeutic regime for patients. “But we need to understand a lot more things before then,” Valente admits.

In the meantime, there’s a palpable excitement in industry circles about the new approach. “We’ve opened up a new way of thinking and more and more researchers are thinking about going down this path,” Valente concludes.