For around 18 months, immune globulin (IG) has been in shortage globally. Derived from donated human blood plasma, IG is an antibody replacement and immune modulation therapy, preventing those with immune deficiencies, both primary and secondary, from developing serious, potentially life-threatening infections. It was developed in the second world war, and first became available to patients from the early 1950s.

The acute shortage of this life-saving drug has forced doctors to either cancel or attempt to ration infusions of IG to those most at need; there has been a rising trend of IG being prescribed experimentally for off-label indications, such as fungal infections and infertility.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Non-profit patient organisation the Immune Deficiency Foundation’s president and CEO John Boyle notes the charity has been approached by numerous patients concerned that their doctors have told them that they are “having trouble getting hold of the product and they don’t know when it is going to be available”.

Since this is a genuinely life-saving drug for many patients, there is an urgent need to understand the causes of this shortage to rectify the situation quickly and try to prevent it happening again.

A miracle drug: IG “keeps us alive”

Boyle, who has a primary immune deficiency, describes IG as a miraculous drug.,

“If this therapy had not existed when I was six months old and became critically ill, I would have died,” he says. “IG is what keeps many of us alive…and allows [us] to live normal, productive lives.”

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

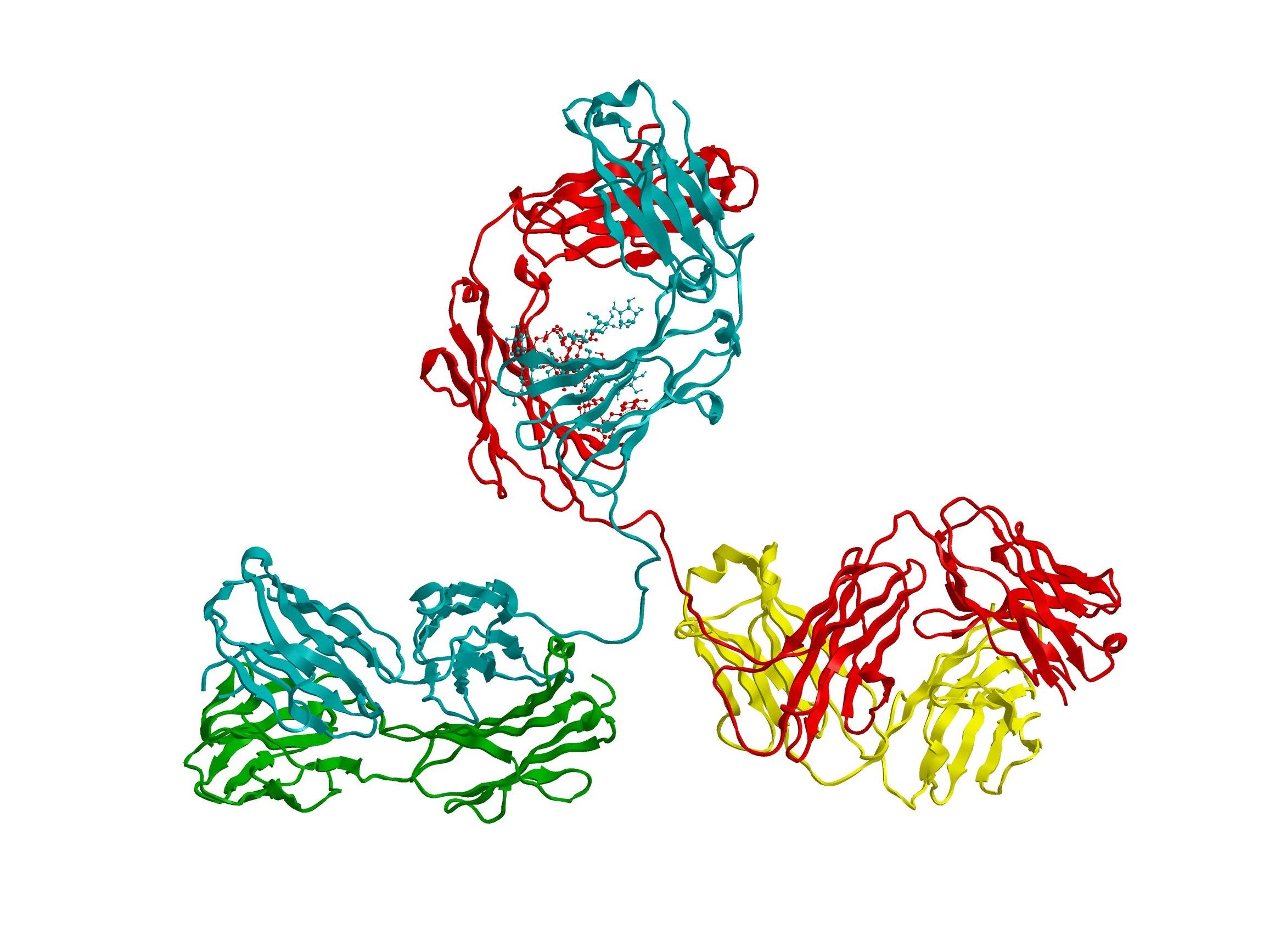

By GlobalDataIG is the only effective treatment for primary immune deficiencies, and it has also proven to be clinically effective in secondary immune deficiencies, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), autoimmune disorders like Kawasaki disease, neurological conditions like multiple sclerosis, as well as complications that develop following cancer treatment and bone marrow transplants.

For those with immune deficiencies “where they do not produce antibodies naturally, then it is a replacement therapy”, which increases both the quality and quantity of antibodies in their system, Boyle explains. Whereas for people with autoimmune conditions, such as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, IG performs an immune modulation role, where it “reigns in, moderates and modulates their immune system to more desirable levels”.

What is causing the IG shortage?

Although Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association (PPTA) president and CEO Amy Efantis notes there is not a single cause of the shortage, or “access issues” as the trade association characterises it, the primary problem seems to be that demand has outstripped supply.

Boyle explains this is an issue because as demand increases, “you can’t really ramp up production” of IG.

This is because there is between seven and 12 months of lag time to manufacture and produce an IG product that can be infused into a patient, meaning that although “companies are continuing to build greater and greater capacity”, as Efantis notes, “if access issues become acute, you can’t ramp up production or adoption in a month or two.”

Efantis identifies two major causes of this surge in demand: better diagnosis of immune deficiencies and more use by patients with secondary immune deficiencies, such as cancer patients and people with neurological diseases.

However, Boyle also notes the role of experimental, off-label uses of the drug where it might have a “more incremental benefit” to patients, rather than being life-saving, as it is for immune deficiency patients. Boyle sees this element as one of the ways this case differs from previous shortages, such as the disruption in the 1990s, which he explains was caused by changes in regulatory oversight of the manufacturing process.

He concludes: “A distributor might be telling a hospital or specialist pharmacy, we can get you the same as what we got you last month, but if you have new patients, we can’t cover that.”

Not a generic: role of contracts in stunting access

Another element that differentiates this shortage from previous IG-specific shortfalls is that access issues are only in specific products, rather than in IG in general.

“One thing to remember about IG is there isn’t a one size fits all therapy,” Efantis points out.

Boyle adds: “IG is not generic, people do react differently to different products.” This means that once “a patient is stabilised on a particular IG product, their immunologist tends to keep you on that specific product”.

Efantis gives the example of a boy called Charlie. “Charlie is one of four children, all four have an immune deficiency and are on four different IG therapies,” she explains. ”Charlie’s brother was switched to a different therapy that made his brain swell. The heterogeneity of the products is a really important thing to recognise.”

The fact that patients are so reliant on one product means that they can be easily affected by what reimbursement policies and national tenders are happening in other countries. “If more of product x starts going to one country or market, then patients elsewhere will need to fill the gap from elsewhere.” says Boyle.

However, their local hospital or specialist pharmacy may not be able to provide the product they need as they have only signed a contract with one manufacturer, which, due to the manufacturing challenges involved in producing IG products, cannot suddenly ramp up their production.

No evidence of medicine stockpiling

Sometimes when a drugs shortage starts to emerge, hospitals begin to stockpile medicines to protect patients in the event that the pipeline of the drug dries up completely. Unfortunately, this usually only exacerbates the shortage and often further disrupts the supply chain.

“From all we’ve seen, and most people are very open with us, no [stockpiling] has not been an issue,” says Boyle. “Everyone has an incentive to move that product as quickly as they can.” He believes that stockpiling would be “unconscionable”.

In addition, unlike traditional drugs, plasma-derived products have a very short shelf life, so stockpiling would probably not be effective for this product. Enfantis notes manufacturers are “careful” about not wasting precious plasma by sitting on donations or producing surplus IG products.

Plasma drive: preventing future shortages of life-saving IG

In the short term, Boyle calls for the medical community to “be thoughtful about how [IG] is being used”, and to prioritise patients for which this therapy is actually proven to be life-saving.

In the longer term, both Boyle and Efantis note there is a need to focus on sourcing more plasma donations to keep pace with this growing demand. It is important to remember that “[for] a patient with an immune deficiency, [they need] around 130 donations of blood plasma” per year, according to Enfantis.

Boyle points out that 70% of plasma and plasma-derived products used globally are sourced in the US, and calls for other countries and regions to step up and focus on ramping up local plasma donation.

Increasing plasma donation requires a re-education of how donating blood plasma can save someone’s life. To this end, the PPTA has organised a campaign called ‘How’s your Day’ with the aim of illuminating the unpredictability in the daily lives of patients reliant on IG and other plasma-derived therapies. A strong base of plasma donors lays the foundation for a stronger IG supply chain and more reliable access to the treatment for those who desperately need it.