Political journalist and broadcaster Emma Barnett had always dreaded the monthly arrival of her period, since it first made an appearance in a Manchester department store when she was almost 11 years old.

“I lived with terrible, bone-grinding pain, awful bouts of nausea, debilitating joint weakness and the feeling that I might black out,” she wrote in Vogue prior to the publication of her book Period, which confronts the taboo of menstruation.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

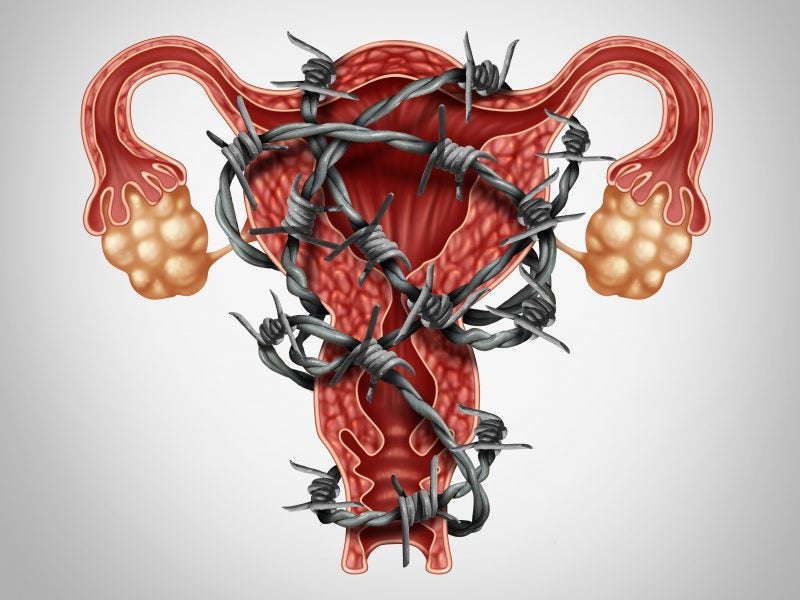

But it wasn’t until Barnett turned 30 and wanted to start a family that she was diagnosed with endometriosis. The disease occurs when cells such as those found in the lining of the womb are found outside the endometrium. It causes heavy, painful periods and can lead to infertility and bowel and bladder problems. It affects around 10% of women.

It can also take a serious toll on mental health. In recently commissioned research from the BBC, half of women with the condition said they had suicidal thoughts. While many admitted to relying on addictive painkillers to get them through the day.

Barnett is not alone in her long road to diagnosis. Women wait an average of seven and a half years between first seeing a doctor about their symptoms and receiving a firm diagnosis of endometriosis.

The problem with pain

High-profile women such as Barnett and actress Lena Dunham are now speaking out about endometriosis, and reports like the BBC one are raising the condition’s profile, but there’s still a lack of awareness and understanding. And there’s also the problem of knowing just what counts as normal when it comes to period pain.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData“Pain is so subjective. And menstrual cramps are the only type of pain that we accept someone should have. But how do you know if yours is more than someone else’s? Almost universally these women are dismissed, told it’s normal, told they should just take painkillers and get on with their lives and stop complaining,” says Dr Hugh Taylor, chief of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Yale New Haven Hospital and a professor at Yale University.

And even if you do get a sympathetic doctor, currently the only definitive diagnostic method for endometriosis is via laparoscopy — where a camera is inserted into the pelvis through a small cut near the belly button. If lesions of endometriosis are found, these can be treated during the procedure. But, many women find the disease and its symptoms occur again within a few years. There is currently no cure.

“Sufferers of endometriosis are yet to find a drug that reduces or stops their pain long term without side effects. Given that most women wait years, maybe even decades, to get a diagnosis, it may be difficult to find participants for clinical trials,” says UK-based GP Dr Diana Gall on the lack of treatment options.

Endometriosis is a poorly understood, under-researched condition, but we do know it requires the hormone oestrogen to occur. That’s why first-line treatment is the contraceptive pill or the hormonal coil, explains Taylor.

“Contraceptive pills are easy and cheap, but they’re not necessarily the best. There’s a pretty high rate of resistance to the progestogen in them. So we see quite a few failures.”

The only real alternative to contraceptive options (often ineffective at relieving pain) or invasive surgery is a class of drugs called gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists. These medicines, such as leuprorelin — usually given as an injection — dampen down oestrogen, which does result in pain relief for many patients. However, GnRH agonists also come with some pretty severe side effects — similar to those of menopause — such as hot flushes, headaches and insomnia.

“The side effect profile on many of these drugs is very unattractive. And one of the things that has not been studied sufficiently is long-term side effects that may be irreversible,” cautions Lone Hummelshoj, chief executive of the World Endometriosis Society, who has experienced the debilitating condition herself.

Bone loss (osteoporosis) is a particular concern, which is why women taking drugs like leuprorelin are advised to only be on them for a short period of time. But after the medication is stopped, the symptoms will often return.

New drug candidates

Taylor believes there are some promising candidates in the pipeline that could make these menopausal side effects less of a worry. In July 2019, AbbVie received FDA approval for Orilissa (elagolix), which also acts on the GnRH receptor but as an antagonist, rather than an agonist. It is taken orally. Orilissa has been approved in two different doses to treat moderate and severe forms of endometriosis in the US and Canada.

“The idea of the agonist is you have to really overwhelm the receptor to block it all. It’s simply full suppression to zero oestrogen. But with the antagonist, you have more control. Not everyone needs full suppression with all the side effects that go along with that,” Taylor reveals.

While hot flushes, night sweats and insomnia may be less severe on Orilissa compared to drugs like leuprorelin, these side effects are still commonly experienced in those taking the GnRH antagonist. And research indicates that bone loss could still be a problem, which is why the higher dose is currently prescribed for only six months. But, add-back hormone therapy, where low doses of oestrogen are given at the same time, could reduce this risk without reawakening the pain, Taylor believes.

“This is the first real movement we’ve seen in decades. There hasn’t been another new drug approved in the US for endometriosis treatment in my career. It’s really exciting that we are seeing some movement.”

Also in clinical trials are two similar candidates in terms of mechanism of action: Myovant’s relugolix (phase iii) and linzagolix from ObsEva (phase ii). Both GnRH antagonists, Taylor hopes there will be more choice for endometriosis patients if these reach market.

Beyond hormones

But, some experts believe therapies that modulate sex hormones aren’t the right solution. And any drug that does so will not be suitable for someone wanting to get pregnant in the near future. This is a key issue for a condition that affects young women.

While we know endometriosis is a hormonally-dependent condition, scientists are still figuring out what causes the disease to develop. There may well be other factors at play. A collaboration between Bayer and Evotec is looking into non-hormonal medications to reduce pain in endometriosis which work by inhibiting a receptor called P2X3.

Taylor’s lab at Yale is exploring the molecular mechanisms that lead to, and regulate, the disease. His group has identified several biomarkers that could help doctors diagnose endometriosis more easily in the future. It would mean that women might not have to undergo surgery to confirm that they have the disease.

“I’m really pushing to eliminate the diagnostic laparoscopy,” reveals Taylor. “There are some people who will have adhesion and fibrosis from the damage done by the endometriosis that the medication won’t change — so there’s a role for surgery in treatment, but not to make the diagnosis. We can often make it clinically. I think we’ll see some biomarker tests developed in the next few years.”

Hummelshoj is hopeful that research efforts, in both academia and industry, will bring about positive change for women who experience severely painful periods.

“I work with the distinct mission that we can prevent endometriosis in the next generation of women. Never mind treating it, wouldn’t it be amazing if we could prevent it?”