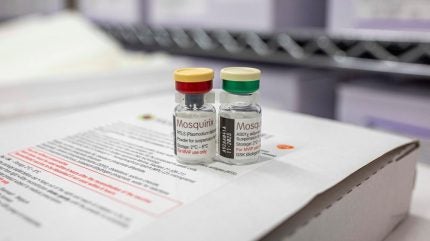

The World Health Organisation-approved malaria vaccine has been the cause of much celebration, but how useful will it be in the fight against the disease? (Photo by Patrick Meinhardt/Getty Images)

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has approved the world’s first malaria vaccine, the fruit of a 34-year, $750m research effort.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Although an enormous milestone in the history of the disease, the vaccine, which has been approved for use in African children aged under five, is only 30% effective against severe disease and requires four shots.

That is significantly below the WHO’s Malaria Vaccine Technology Roadmap goal of 75% efficacy.

Malaria killed 409,000 people in 2019, according to the WHO. If the vaccine were given to children in all high-risk countries, one study suggests, it could save 23,000 lives per year.

Such a roll-out would require 100 million doses each year, but GlaxoSmithKline, which co-funded the vaccine’s development, has only pledged to provide 15 million low-cost doses per year.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataAre vaccines the best way to combat malaria?

At an estimated $5 per dose, public health experts have called into question the cost effectiveness of such a roll-out.

One study estimated that for the vaccine to save one disability-adjusted life year, a standard metric in public health cost-benefit analyses, the cost would be approximately $200. Insecticide-treated mosquito nets and seasonal malaria chemoprevention (a regimen of anti-malarial medications for healthy children), by contrast, can save one disability-adjusted life year for just $27 and $68, respectively.

If the vaccine roll-out diverts funding from these interventions, which remain far from universal, the net effect could be negative.

In August, a study found that the vaccine’s efficacy against childhood malaria deaths could be as high as 73% when taken at the correct time and in conjunction with seasonal malaria chemoprevention.

However, seasonal malaria chemoprevention is currently only implemented in six of the 11 countries with the highest malaria burden. The joint intervention would also require annual booster shots.

Is progress being made in the fight against malaria?

Despite the lack of an available vaccine until now, significant progress has been made against malaria in recent decades.

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), a US-based think tank, estimates that malaria was responsible for anywhere between 500,000 and 1.4 million deaths globally in 1990.

By 2019, that number had fallen only slightly – to between 300,000 and 1.2 million, a decrease well within the estimate’s margin of error. From 1990 to 2019, the annual number of malaria deaths in Nigeria rose by 28%, from 149,000 to 191,000.

In that same period, however, the country’s population more than doubled. In any society, more people means more deaths – including deaths from whatever causes are common in that society, such as malaria.

In Nigeria, the number of malaria deaths per 100,000 people fell from 165 in 1990 to 89 in 2019, a mark of significant progress in fighting the disease.

Across sub-Saharan Africa, deaths from malaria per 100,000 people fell from 121 in 1990 to 94 in 2010, and to 55 in 2019.

In the past decade, however, many countries have seen their anti-malaria efforts stall or even reverse. Since 2010, malaria deaths per 100,000 people have increased by 32 in Mauritania, 12 in Somalia, eight in Namibia and seven in Kenya, according to IHME data.

In 2020, the WHO warned that an increase in malaria deaths in Africa due to disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic will likely dwarf direct Covid deaths on the continent.

The organisation’s 2021 World Malaria Report is due to be published later this year, but last year’s report predicted that 2020 would be the first year in decades to see a rising global death toll from the tropical disease.

Will Covid pandemic boost malaria fight?

The massive public investment in vaccine technology and distribution during the Covid-19 pandemic has given rise to several other possible malaria vaccines, shots which may prove significantly more effective than GlaxoSmithKline’s.

In April, an anti-malaria vaccine developed by the Oxford University team behind AstraZeneca’s Covid-19 vaccine became the first to demonstrate efficacy above the WHO’s 75% benchmark. The researchers hope that the vaccine can be rolled out within two years, with the Serum Institute of India promising to produce 200,000 doses annually.

BioNTech has announced plans to develop an mRNA-based anti-malaria vaccine, with clinical trials expected to begin by late 2022.