Nearly 80 million people in the US and six million in the UK are eligible for a Covid-19 vaccine, yet remain unvaccinated. As the Delta variant surges, global governments have doubled down on their efforts to convince this population to undergo inoculation. For many, these communications have taken on a distinctly blunt tone.

In a recent speech, President Joe Biden directly addressed the vaccine hesitant, saying: “We’ve been patient, but our patience is wearing thin. And your refusal has cost all of us.” Meanwhile, England’s Chief Medical Officer Chris Whitty expressed a similar sentiment, saying many people who discourage Covid-19 vaccination “know they are pedalling untruths but they still do it”, and “should be ashamed”.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

However, communications specialists have their reservations about how well this forceful messaging really works in practice.

Penn State University professor of media effects S. Shyam Sundar says this tone “seems to be striking the wrong chord with a sizable minority who are refusing to get vaccinated.”

“I am wondering if that is because the message has been mostly directive – do this, don’t do this – rather than suggestive,” Sundar continues. “We know from research on health communications that directive messages can evoke reactance in the form of anger and counter-argumentation. That is unfortunately what we are seeing from the unvaccinated.”

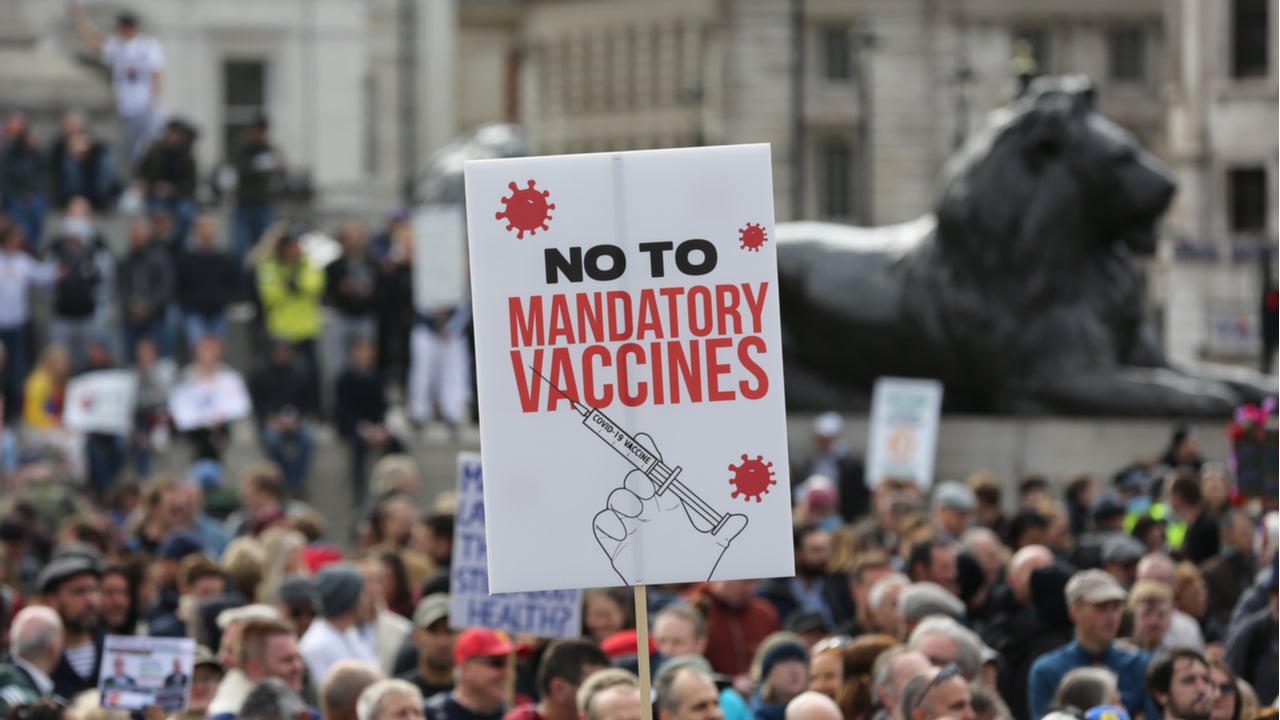

For some individuals, directive messages – like the UK government’s heavily criticised ‘Can you look them in the eyes?’ campaign, which ran across digital and traditional media – can trigger hostile reactions. The messages are seen to threaten the free will of the viewer by dictating what they are and aren’t allowed to do, which in turn is perceived as a threat.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataWhen these individuals sense this threat to their freedom they become motivated to restore it by attempting to do what is prohibited or refusing to carry out recommended behaviours. This means that if messaging about the Covid-19 pandemic is too forceful or scolding, it could inadvertently lead to people rejecting vaccination or public health guidance.

Misinformation goes digital

This affect of Covid-19 communications felt particularly strongly in the digital sphere, where the pandemic has had a significant impact on people’s actions and behaviours. Whitty’s comments, for example, were made following an inquiry from a journalist about his take on an unsubstantiated story posted on Twitter by rapper Nicki Minaj, who claimed that a family friend became impotent after his Covid-19 vaccine. Minaj has over 22 million followers on the social networking platform.

Use of social media and digital platforms rose sharply during the initial outbreak, when people were attempting to remain connected to each other during lockdowns – and seek out information about Covid-19. But it’s in the digital sphere where a message can most quickly be misconstrued, and where misinformation can spread the fastest. Campaigns to spread false and misleading information about Covid-19 vaccines have flourished on social media, but this isn’t just confined to Facebook and Twitter.

Ivermectin, a drug primarily used for horse deworming, has been promoted online as an alternative treatment to Covid-19 vaccination. While the drug has some limited applications in human health, large doses can be dangerous and studies indicate that people with Covid-19 who take the drug not only experience no benefits but their symptoms can actually get worse.

Forbes reports that several patients have spread misinformation about the drug through online reviews on the websites of online pharmacies, claiming that ivermectin is completely safe and helped them survive Covid-19.

Misinformation like this is almost impossible for public health bodies to counter permanently – antivaccine conspiracy theories are nearly as old as vaccination itself – but encouraging members of the public to get vaccinated or obey pandemic-related legislature with a directive or forceful tone appears, for some, to push them further into it instead of scare them straight.

How can digital Covid-19 communications change their tune?

Sundar says digital platforms can be leveraged to help encourage Covid-19 vaccination without triggering knee-jerk hostility. Research carried out by Sundar and his team has found that individuals are more likely to be receptive to public health messaging if it has a lot of social media likes from their peers.

“Public health bodies can leverage the tools of digital media to showcase the bandwagon surrounding pro-vaccine messages by prominently displaying popularity metrics such as number of likes,” he says. “This will likely be effective if the likes are from the receiver’s own social network or from others who share similarities in background, demographics and other social aspects.

“Digital media messages promoting vaccination should also offer message recipients opportunities to comment on the messages so that they know that their concerns are being heard and they feel like they have some agency in the matter. This can dissipate some of their resistance.”

As well as centring engagement metrics and encouraging digital discourse, Sundar says public health bodies should target customisable digital spaces that users design to reflect themselves.

“We could use digital media technologies to personalise vaccine messages in ways that strengthen their sense of identity, or place those message in a person’s customised space online,” he says.

His research indicates that seeing a public health message in a personalised space – like a Twitter feed curated to reflect the users’ interests, or a dating app which shows users a certain type of profile they have chosen to see – feels less threatening to viewers, because they are seeing it in a space designed to reinforce their own identity. Targeting pro-vaccination messaging at these spaces could therefore prove more fruitful than other platforms.

It can be hard to know how to encourage vaccine uptake at this stage of the pandemic – evidence of the vaccines’ efficacy and of the seriousness of Covid-19 is all too apparent, but this information alone isn’t always enough. What is clear is that a digital communications approach to Covid-19 that comes across as commanding or insistent can actually end up having a negative impact on uptake. Seeking to encourage vaccine-hesitant people in a way that feels engaging and empowering, instead of urging begrudging compliance, could yield better results.