The approval of Biogen’s aducanumab by the FDA last week marked the first new Alzheimer’s drug to be okayed for patients in almost 20 years. Some have hailed the decision as a historic moment in the fight against a devastating, incurable disease – but the move is not without its controversy.

In the wake of the drug’s approval, three members of the FDA’s advisory committee resigned from their posts, with one writing in his resignation letter that the FDA’s authorisation “made a mockery of the committee’s consultative process”. Back in November, the advisory panel voted almost unanimously against the approval of aducanumab, known commercially as Aduhelm, with ten voting against, one abstaining and none voting in favour.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

The FDA’s decision to overrule an advisory recommendation is rare. Joel Perlmutter, a professor of neurology and one of the three experts who quit the FDA’s advisory panel in protest, said in a statement: “as an advisory committee member, I am extraordinarily disappointed that our unbiased advisory committee review was not valued.”

Accelerated Approval

Aducanumab was authorised using the Accelerated Approval pathway, which grants earlier approval for drugs that fill an unmet medical need. The programme relies on surrogate endpoints that indicate the drug is likely to be of clinical benefit to patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but do not guarantee it.

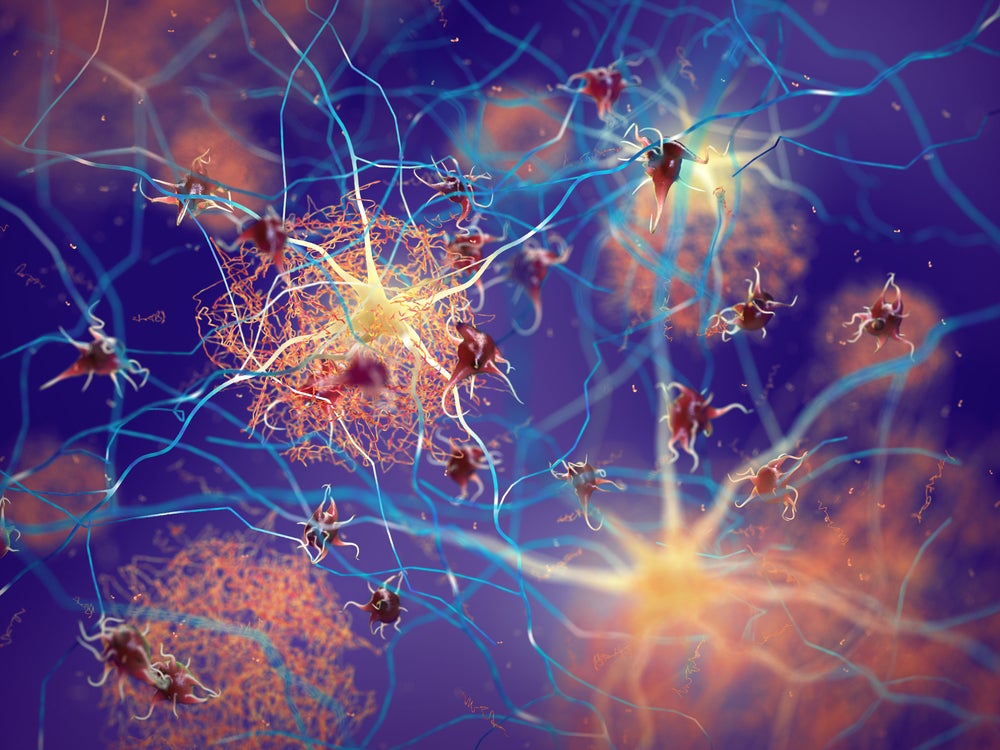

The FDA said in a statement published last week that it was aware of the controversy surrounding the approval of aducanumab. The drugs regulator said Biogen’s drug appeared to target the amyloid-beta (A-beta) plaques in the brain that are widely believed to be the underlying cause of Alzheimer’s, and that the trial showed a reduction in these plaques that is “expected to lead to a reduction in the clinical decline of this devastating form of dementia”.

The aducanumab programme consisted of two Phase III trials; one met the primary endpoint, showing reduction in clinical decline, while the other did not. The FDA said, however, that the drug “consistently and very convincingly reduced the level of amyloid plaques in the brain in a dose- and time-dependent fashion” in every study.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataDrug companies are required to carry out Phase IV confirmatory trials to verify their products’ benefit after approval; if the drug doesn’t work as intended, the FDA can pull it from the market. Biogen CEO Michel Vounatsos told CNBC the company would have nine years to complete the post-approval trial for aducanumab.

Questionable efficacy

While the FDA has declared aducanumab will likely be beneficial to patients, numerous experts have argued that the data available is insufficient to establish this.

In the statement made following his resignation, Perlmutter expressed concern about the decision to make amyloid-beta plaque the surrogate endpoint of the study, given that there isn’t enough evidence to assert that removing the plaques improves cognition in AD patients.

“There is insufficient evidence that A-beta clearance predicts clinical benefit,” he said. “This is a major problem.”

What’s more, Biogen suspended the Phase III trials that aducanumab’s approval is based on in 2019, after an independent data monitoring committee advised that the drug was unlikely to meet its endpoints. Despite the setback, the company applied for FDA approval that same year, stating that high doses of aducanumab appeared to significantly reduce cognitive decline in some patients.

The infusion of aducanumab is also associated with amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), which causes swelling and bleeding in the brain and was observed in 41% of trial participants taking the drug. Perlmutter said there are concerns about whether these “scattered lesions in the brain” can lead to neurologic abnormalities.

Critics of aducanumab have argued that its approval could see the bar for FDA authorisation drastically lowered in the future. Medicinal chemist Derek Lowe wrote in a blog post: “So the FDA has, for expediency’s sake, bought into the amyloid hypothesis although every single attempt to translate that into a beneficial clinical effect has failed. I really, really don’t like the precedent that this sets: what doesn’t get approved, now?”

Hefty price tag

As well as concerns about aducanumab’s efficacy, Biogen has come under fire for the steep price attached to the new treatment. While drug pricing watchdog ICER determined that a fair cost for a therapy with such limited evidence of efficacy would fall between $2,500 and $8,300, Biogen has slapped an eye-watering $56,000-per-year price tag on the drug.

ICER said in a statement: “Our report notes that only a hypothetical drug that halts dementia entirely would merit this pricing level. The evidence on aducanumab suggests that, at best, the drug is not nearly this effective.

“At this price the drug maker would stand to receive well in excess of $50bn per year even while waiting for evidence to confirm that patients receive actual benefits from treatment.”

Even advocates for the drug have slammed Biogen over the drug’s price. The Alzheimer’s Association called the cost “simply unacceptable”, and said it “will pose an insurmountable barrier to access, it complicates and jeopardises sustainable access to this treatment, and may further deepen issues of health equity”.

A contentious issue

Despite the controversy surrounding the drug, many have welcomed its approval. Richard Morris, Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Edinburgh, said despite concerns about the clinical benefit aducanumab provides, “it is great news that a start has finally been made in the search for treatments targeting the causes of Alzheimer’s disease”.

It’s understandable that some experts and patient groups are celebrating the drug; over six million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s, and the few treatments that are currently available are not able to delay the onset or reduce the progression of the devastating disease.

Still, it is crucial that any drug made available to Alzheimer’s patients actually benefits them and does not derail the work being done to meaningfully improve their lives.

“Approval of a drug that is not effective has serious potential to impair future research into new treatments that may be effective for treating AD,” Perlmutter said. “For example, new AD studies may be required to no longer compare an investigational drug to placebo – as would be the standard – but rather may have to compare to aducanumab.

“Enthusiasm, from either potential volunteer participants or funders, for new treatments may wane due to thinking that we already have an effective treatment, when in fact we do not.

“These are potentially very serious issues for helping all of the people and families affected by AD.”