If you want to better understand how our genes can predispose us to disease, look to sickle cell disorder (SCD). It’s one of the oldest known and most common genetic disorders and affects millions of people around the world. It is particularly common in people with an African or Caribbean family background.

Approximately 300,000 individuals are born every year with the condition that arises due to a mutated gene on chromosome 11. This slice of DNA encodes the red blood cell protein haemoglobin which binds to oxygen from the lungs to deliver it to the rest of the body.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

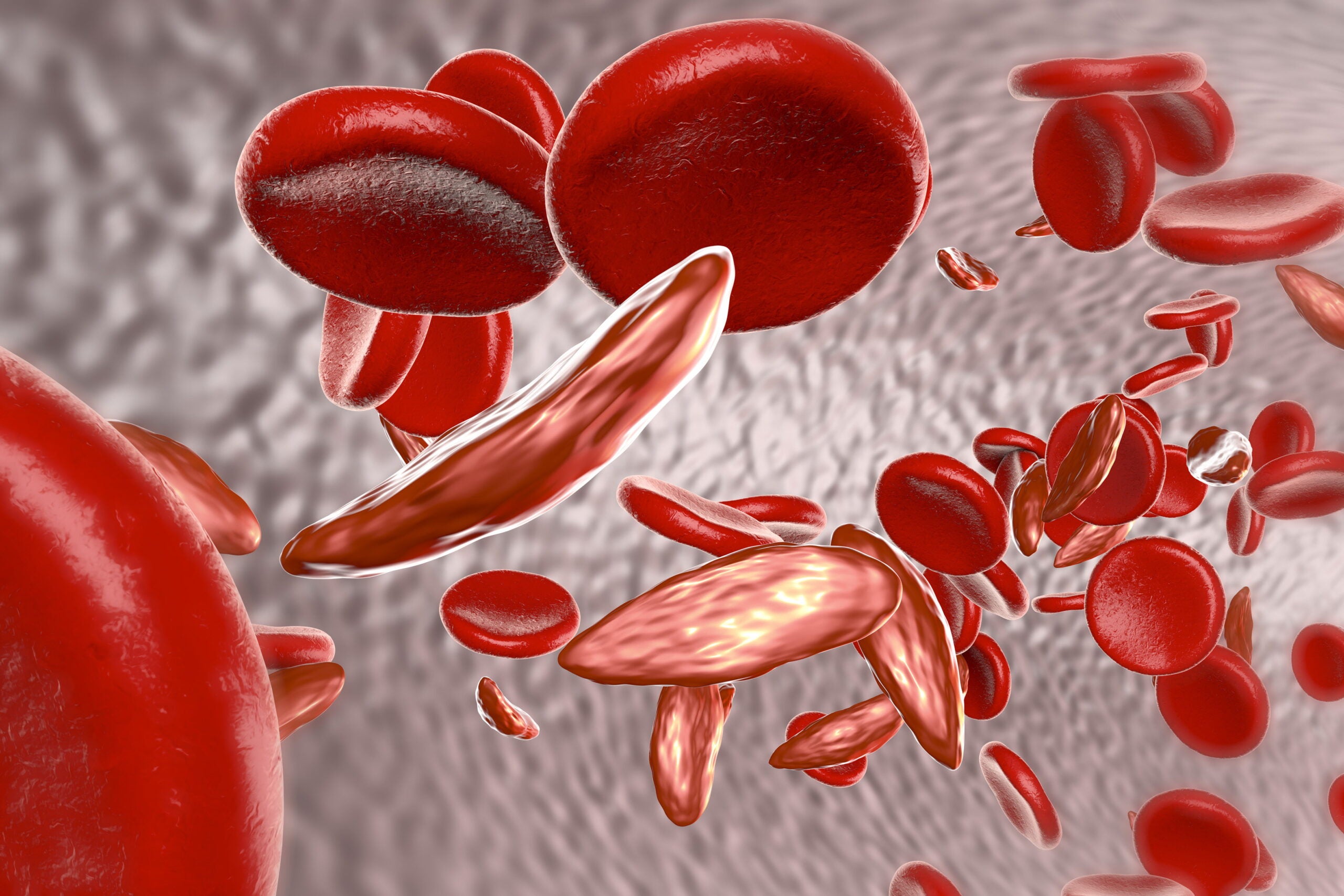

Normally haemoglobin makes red blood cells smooth and round, a shape that allows them to glide through blood vessels with ease. But people with SCD have blood cells that assume a sickle shape which makes it much harder for them to travel around the body to deliver oxygen.

This leads to anaemia but SCD can also cause acute episodes of pain (often called ‘pain crises’) and sometimes life-threatening complications such as organ problems and infections. People with the condition are frequently hospitalised. And unsurprisingly, the disease can also have a profound effect on a patient’s emotional health.

While researchers have known about the genetic cause of SCD for decades, only recently have scientists developed tools that could potentially fix the genetic error that causes the disease.

Experimental therapies involve extracting cells from a patient, altering them in the laboratory and reintroducing them to the patient in a procedure that’s similar to a bone marrow transparent.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataIf validated in clinical trials, this type of treatment could be a game-changer for people living with SCD. But patients in low-and-middle-income countries might not be able to access this form of therapy as it will require robust hospital infrastructure which is not available in many regions where SCD is particularly prevalent.

One-time treatment

In February, pharmaceutical giant Novartis announced it has entered into a three-year $7.28 million grant agreement with the Gates Foundation to discover and develop a gene therapy for SCD which can be used in lower-income countries.

“Existing gene therapy approaches to sickle cell disease are difficult to deliver at scale and there are obstacles to reaching the vast majority of those affected by the debilitating disease,” said Jay Bradner, a haematologist and president of the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research (NIBR) in a statement.

“This is a challenge that calls for collective action, and we are thrilled to have the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in addressing this global unmet medical need.”

Novartis says it wants to develop an in vivo gene therapy for SCD that would only need to be administered once, directly to the patient, without needing to modify the cells in a laboratory first. If successful, it would mean someone with SCD wouldn’t have to endure long or repeated hospital stays. And developing countries wouldn’t need specialised lab infrastructure to offer the treatment.

The pharmaceutical company has been researching sickle cell disease and working towards treating the condition for over 40 years. In October 2020, the European Commission approved its drug Adakveo (crizanlizumab) for pain crises in patients with SCD. It is the first targeted sickle cell disease therapy for the reduction and prevention of this SCD complication.

The antibody therapy works by binding to P-selectin, a cell adhesion protein that plays a crucial role in vaso-occlusion – a hallmark symptom of SCD that occurs when platelets and white blood cells get stuck together. This causes immense pain.

“Clinical data showed that use of Adakveo led to a significant reduction in the rate of pain crises and to fewer days spent in hospital,” explains a Novartis spokesperson. “Pain crises disrupt patients’ lives physically, socially and emotionally – and can increase risk of organ damage and early death.”

Cut-and-paste genetics

At the moment the only approved therapies for SCD like Adakveo target the symptoms of SCD rather than the cause. But experts hope that genetic therapies, if approved and validated, could cure the disease for good.

Novartis says it has developed a potential SCD treatment based on Intellia Therapeutics’ gene-editing CRISPR technology – first discovered by Jennifer Doudna at the University of California, Berkeley who was awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The pharmaceutical company has confirmed its genome-editing SCD candidate is in early-stage clinical trials.

SCD is a promising application for gene-editing technology as it arises from a single genetic mutation. CRISPR essentially works by cutting out the faulty gene and replacing it with the correct one. And many experts are hopeful the technique could have applications in treating numerous diseases such as cystic fibrosis, cancer and HIV.

Novartis had already established several public-private partnerships aimed at improving the lives of people with the condition in sub-Saharan Africa.

“Specifically, we are focused on developing a comprehensive approach to screening and diagnosis, treatment and disease management, training and education, and elevating basic and clinical research capabilities,” says the company spokesperson. “These efforts are intended to help prepare healthcare systems for future innovations in the treatment of sickle cell disease.”

And the Gates Foundation has a long history of supporting innovative treatments to sub-Saharan Africa. Novartis says it plans to leverage this expertise during the early stages of the single-use SCD genetic therapy project. This will ensure access and distribution for lower-income countries is mapped out at the very start of the drug development process.

“Gene therapies might help end the threat of diseases like sickle cell, but only if we can make them far more affordable and practical for low-resource settings,” said Trevor Mundel, president of global health at the Gates Foundation in a statement.

“What’s exciting about this project is that it brings ambitious science to bear on that challenge. It’s about treating the needs of people in lower-income countries as a driver of scientific and medical progress, not an afterthought.”

Cell & Gene Therapy Coverage on Pharmaceutical Technology supported by Cytiva.

Editorial content is independently produced and follows the highest standards of journalistic integrity. Topic sponsors are not involved in the creation of editorial content.